A Guest Post by Adam Chilton.

In 1946, the United Nations created an organization charged with promoting and protecting human rights around the world called the Commission on Human Rights (CHR). The CHR was frequently criticized, however, because the countries elected to serve on it were notorious human rights violators. For instance, the Executive Director of Human Rights Watch once compared the CHR to “a jury that includes murderers and rapists, or a police force run in large part by suspected murderers and rapists who are determined to stymie investigation of their crimes.”

In 2006, the UN replaced the CHR with a new body known as the Human Rights Council (HRC) that had new membership rules and election procedures designed to solve the problems that plagued the CHR. In a new short paper, Rob Golan-Vilella—a student at the University of Chicago Law School—and I examine whether the 2006 UN reform actually produced a better “jury.”

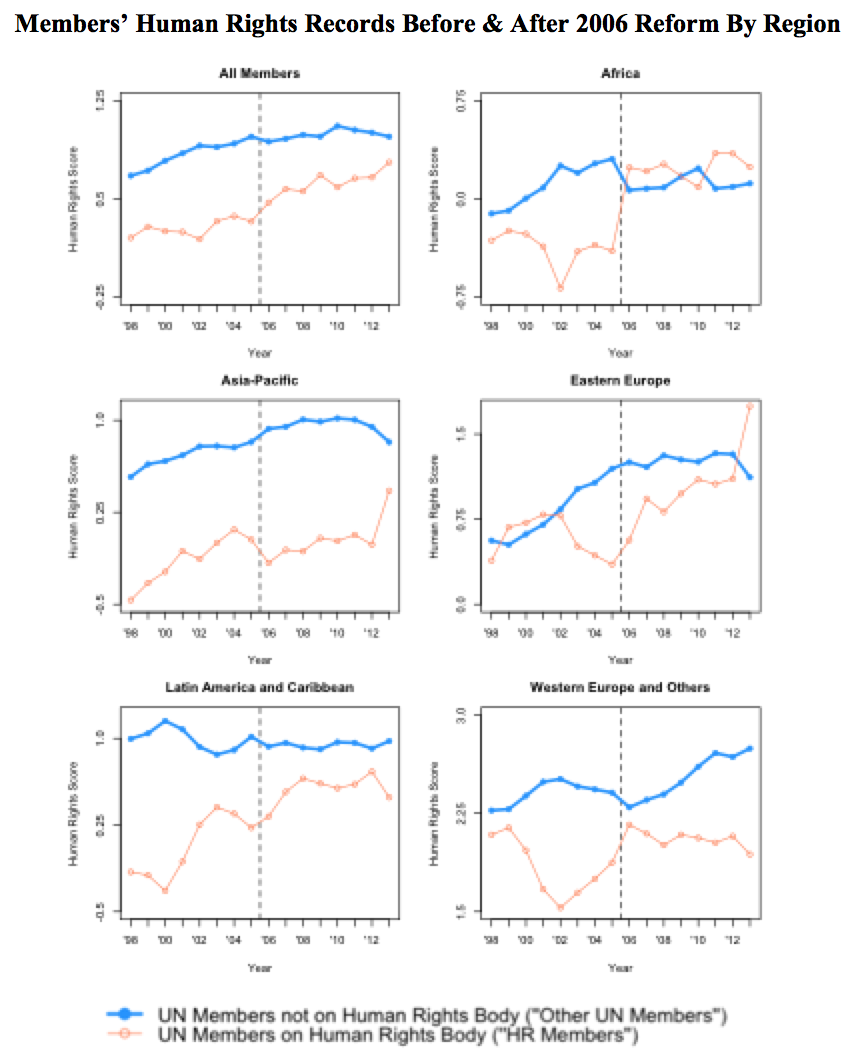

The above figure presents our primary results. The top left panel shows that members of the human rights bodies consistently had worse records than the other UN members from 1998 to 2013 (eight years before and after the 2006 reform), but the gap did close a little after the creation of the HRC in 2006. Since the elections to the human rights bodies occur by region, the rest of the panels show the results by UN region. They reveal that in some regions the 2006 reform largely closed the gap (e.g. Africa), but in other regions the effects were much more modest (e.g. Asia-Pacific).

Why does the gap persist? In the paper we show that when there are contested elections, countries with better human rights records typically win. The problem is that—perhaps because they think they won’t win or don’t care about being a member—countries with good human rights records frequently aren’t candidates in the elections for these bodies.

If you’d like to know more, our paper is up on SSRN and has published by the Harvard International Law Journal Online. (Note: Eric previously posted some of the initial graphs I made on this topic.)

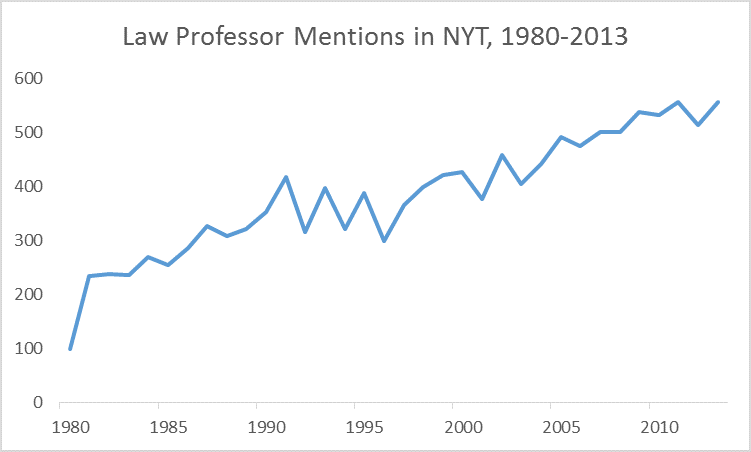

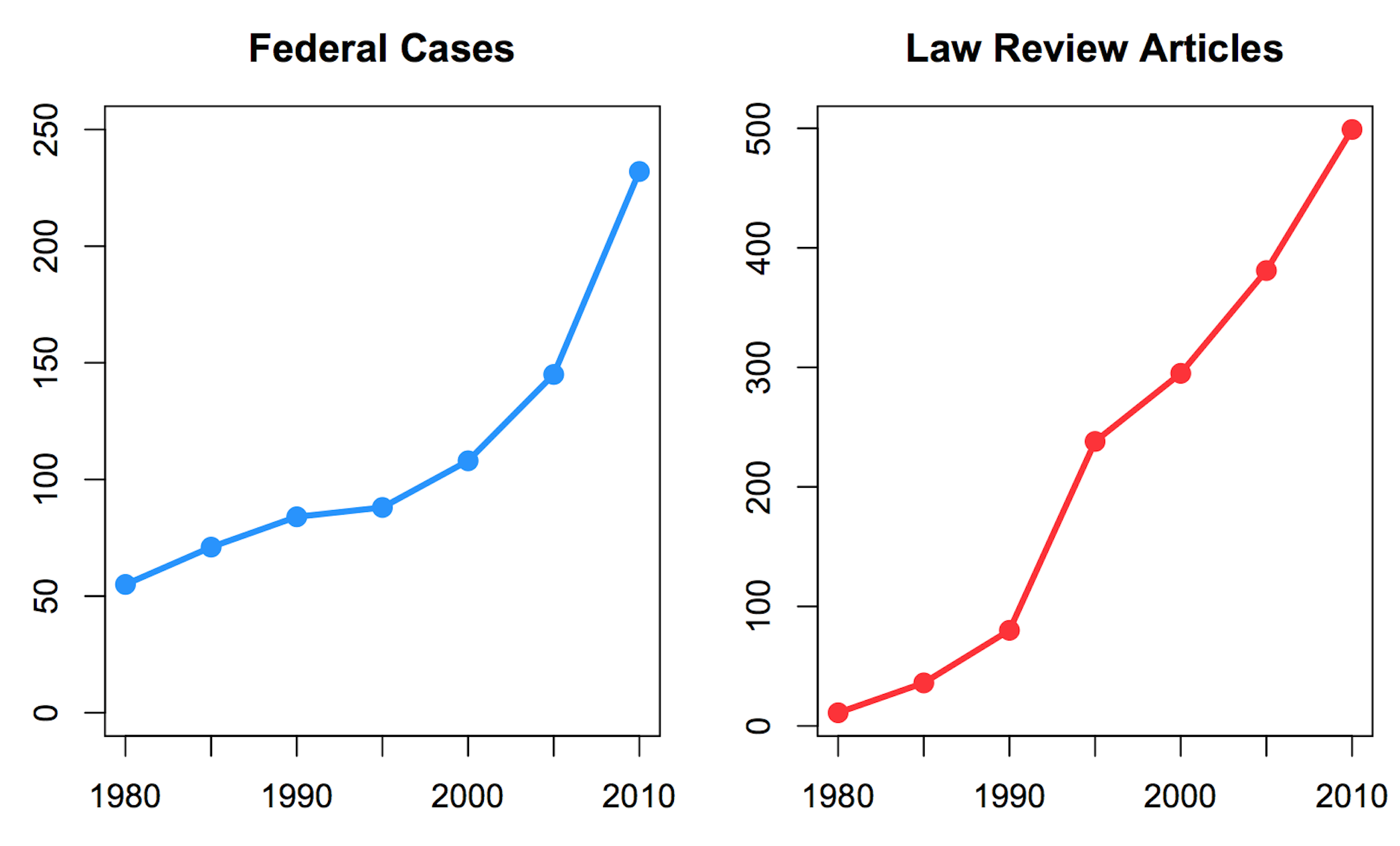

Some revolutions take place with a bang. The empirical revolution in legal studies–and by this I mean rigorous data analysis–was hardly perceptible at first but now empirical work is everywhere. Much of the most interesting work being done right now in the legal academy–in such diverse fields as civil procedure, bankruptcy, international law, and constitutional law– reflects the rigorous statistical methods that Ted championed. At least 5 members of my faculty are trained in statistical methods, and several others do statistical work via collaborations. Twenty years ago hardly anyone did. Ted provided important institutional support for empirical legal scholarship but, most important, served as a model for those who followed him. I’m not sure he received sufficient recognition for his important methodological contributions to legal scholarship in his lifetime. Our paths crossed only a few times but each time it was terrifically rewarding for me. He will be sorely missed.

Some revolutions take place with a bang. The empirical revolution in legal studies–and by this I mean rigorous data analysis–was hardly perceptible at first but now empirical work is everywhere. Much of the most interesting work being done right now in the legal academy–in such diverse fields as civil procedure, bankruptcy, international law, and constitutional law– reflects the rigorous statistical methods that Ted championed. At least 5 members of my faculty are trained in statistical methods, and several others do statistical work via collaborations. Twenty years ago hardly anyone did. Ted provided important institutional support for empirical legal scholarship but, most important, served as a model for those who followed him. I’m not sure he received sufficient recognition for his important methodological contributions to legal scholarship in his lifetime. Our paths crossed only a few times but each time it was terrifically rewarding for me. He will be sorely missed.