Marcel Kahan and Edward Rock have posted a paper on SSRN that asks why “the rhetoric around a variety of high profile corporate governance controversies … cannot be justified by the material interests at stake,” while at the same time “shareholder activists are oddly reluctant to pursue issues that may have a more material impact.” The answer was anticipated by the legal realist Thurmond Arnold, who argued that a great deal of law is supposed to reflect certain myths and taboos believed by the public but that couldn’t practicably be enforced:

We celebrate our ideals of chastity by constantly engaging in wars on vice. We permit prostitution to flourish by treating it as a somewhat minor crime and never taking the militant measures which would actually stamp it out. The result is a sub rosa institution which organizes the prostitutes after a fashion, at least to the extent that there never seems to be any shortage in our large cities. …

Thus in those days anyone who attacked the “Trusts” could achieve the same public worship as a minister of the gospel who had the energy to attack vice. It was this that made Theodore Roosevelt a great man. Historians now point out that Theodore Roosevelt never accomplished anything with his trust busting. Of course he didn’t. The crusade was not a practical one. It was part of a moral conflict and no preacher ever succeeded in abolishing any form of sin.

Kahan and Rock add:

Arnold seems to have saved his most savage (and sincere) condemnation for those poor well-meaning fools who would endeavor to make us live up to our articulated principles because doing so would destroy necessary institutions and cause serious social harm.

They conclude that the myth of corporate governance is that shareholders control firms when in fact they cannot, which means that we must trust managers with billions of dollars and hope for the best. Any attempt to constrain managers would render the corporate form unworkable because shareholders cannot, practically, manager the corporation. Activists maintain their pay and prestige by keeping corporate governance battles in the public eye but in fact no one should hope that they succeed, and perhaps they don’t wish to succeed themselves.

As Kahan and Rock presented their enjoyable paper at a corporate governance conference last week, I couldn’t help thinking: isn’t this the story of originalism?

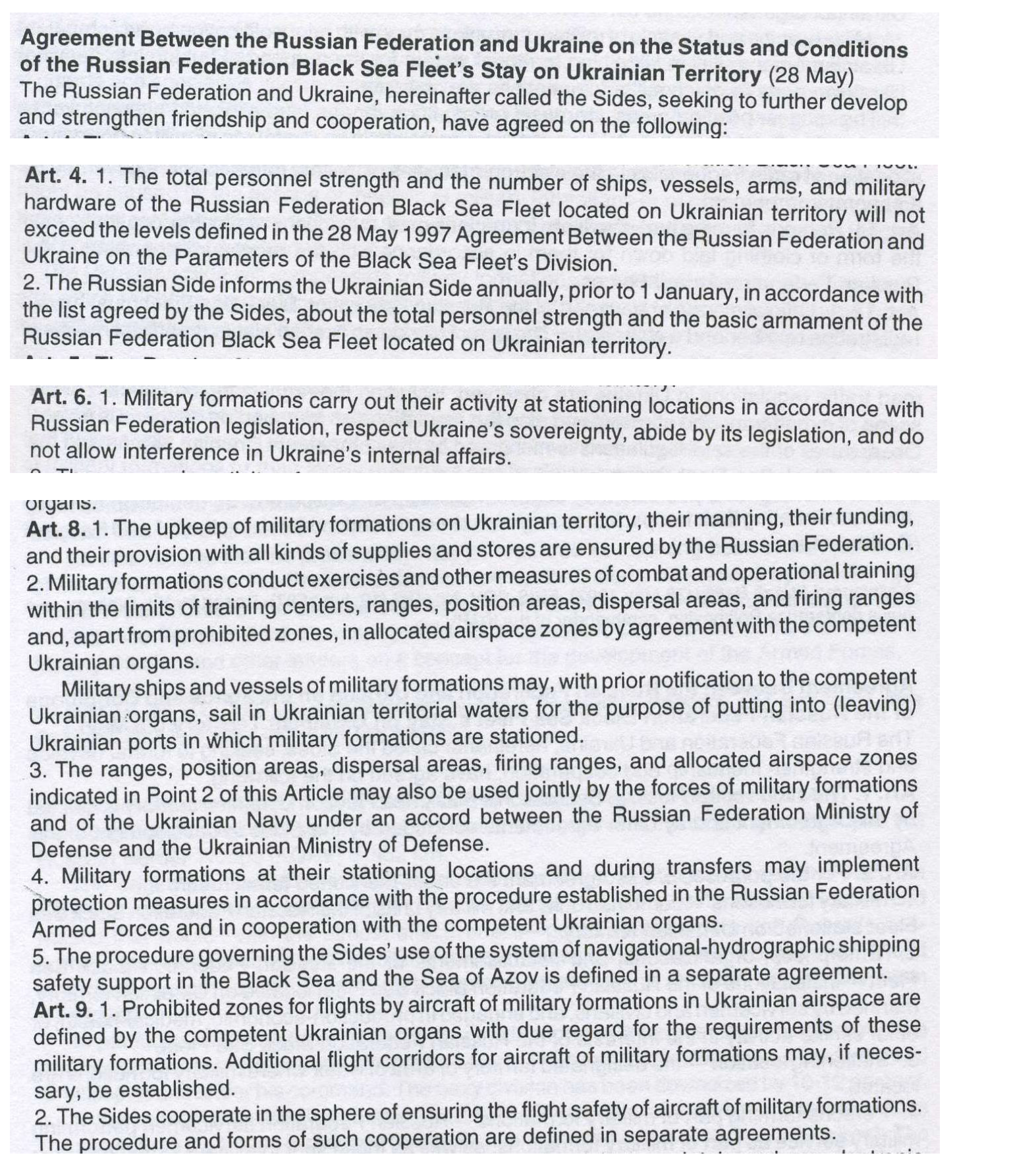

The Crimean parliament has scheduled a referendum for March 16 asking whether Crimea should secede from Ukraine and join Russia. From the standpoint of international law (Ukrainian law may be different), it is not illegal for a territory of a country to attempt to break away and form a new state. But there is a great deal of controversy over when a breakaway territory should be considered a state, which entitles it to enter treaties, join the UN, and so on. One view is that Crimea becomes a state just when other countries regard it as a state. So even if Crimea achieves de facto independence and has a government that controls it, the United States and other countries could block it from being a state just by refusing to recognize it as a state.

The Crimean parliament has scheduled a referendum for March 16 asking whether Crimea should secede from Ukraine and join Russia. From the standpoint of international law (Ukrainian law may be different), it is not illegal for a territory of a country to attempt to break away and form a new state. But there is a great deal of controversy over when a breakaway territory should be considered a state, which entitles it to enter treaties, join the UN, and so on. One view is that Crimea becomes a state just when other countries regard it as a state. So even if Crimea achieves de facto independence and has a government that controls it, the United States and other countries could block it from being a state just by refusing to recognize it as a state.

Peter Spiro (and/or someone else operating the Opinio Juris twitter account)

Peter Spiro (and/or someone else operating the Opinio Juris twitter account)

Will

Will