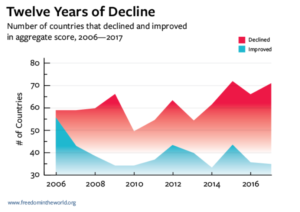

By now it is unmistakable that democracy is in retreat around the world, including in the United States. Freedom House has announced that political and civil liberties have declined for 12 years in a row. While Freedom House is often criticized for its motivations and the accuracy of its ratings, these particular results seem robust, and are consistent with other measures as well as with anecdotal evidence.

By now it is unmistakable that democracy is in retreat around the world, including in the United States. Freedom House has announced that political and civil liberties have declined for 12 years in a row. While Freedom House is often criticized for its motivations and the accuracy of its ratings, these particular results seem robust, and are consistent with other measures as well as with anecdotal evidence.

The decline began in 2006, according to Freedom House, which was just about when human rights scholars began putting together studies that showed that human rights treaties have improved outcomes for countries. Interestingly, an initial set of studies in the 1990s and early 2000s had suggested that human rights treaties did not improve outcomes; the later work was more sophisticated, but in the end it was an exercise in finding correlation and calling it causation. If you extend the scope of analysis to respect for “social and economic” rights (defined usually, if not really accurately, as literacy rates, mortality, education, equal pay for women, etc.), you do seem improvement in most countries, and since nearly all countries ratified human rights treaties a few decades earlier, you have your correlation. One could also, by tinkering with the definitions of political and civil rights, find some improvement as well (though some things, like torture, seemed stubbornly resistant to statistical manipulation).

Then why didn’t human rights treaties stop the slide toward repression, in countries as diverse as Russia, Turkey, the Philippines, Hungary, Poland, Venezuela, Mexico, Honduras, and Rwanda? And we who live in the United States and Europe know things are not well even if democracy remains robust for the time being. The simple answer—which would be platitude if it were not rejected by the human rights community and legions of scholars—is that the treaties were always poorly designed, and not strong enough or taken seriously enough to make much of a difference in how governments treat the public.

The original idea of the treaties was that they would ban the very worst type of behavior exemplified by the Nazis, but as a result of mission creep, today they all but require all countries to be Denmark or Sweden. Yet at the same time, the rights they create are so vague and so riddled with exceptions, while at the same time so frequently in conflict with each other, that nearly any type of government policy could be rationalized. The United States and a few European countries took them a bit more seriously than most, but mainly to use as a cudgel against their enemies or rivals, in the most selective manner possible.

You would think that it would be a good time for scholars and those in the human rights community, government officials and NGOs, to embark on a reassessment. I don’t see one coming. There is a large industry that depends on the illusions that these treaties create; it would gain nothing by exposing them.