I explain why people overestimate the risk posed by the Syrian refugees in Slate. I argue that the xenophobia/nativism/bigotry arguments are unfair.

All posts by Eric Posner

The “take my word for it” theory of separation of powers

With Congress supine and feckless, law professors committed to the rule of law have taken to arguing that executive-branch lawyers can be trusted to ensure that the president does not break the law. That’s the argument, for example, of Trevor Morrison, the dean of NYU Law School; Jack Goldsmith also made this argument, more or less, in his book, Power and Constraint.

But what if a “deeply-sourced” journalist named Charlie Savage writes a 700-page book that shows that executive branch lawyers, in almost all cases, failed to stop the president from breaking the law? Then you double down:

What never shows up in books like Power Wars, and what the public never sees, are the scores of times that lawyers preempt operations and policies – in a phone call, conversation, or preliminary meeting – that are clearly out of bounds. Nor can we ever see the stream of dreamed-up and potentially useful operations and policies that never make it to a conversation because the policymaker knows that the answer will be “no” and thus never asks. In these and related ways, law hems in the President’s decisonmaking by limiting the policy options that reach his desk. A complete assessment of the effect of law on senior national security decisionmaking would need to compare the questionable approvals and fudges we see against the much-harder-to-perceive instances that law constrains by limiting possible courses of action. Reporters cannot easily get at this latter type of information.

And here’s Oona Hathaway (also a former executive-branch lawyer):

Savage must get his information from sources, and those sources often have an agenda or a limited view of the issue at hand. (They are also, it bears mentioning again, often breaking their legal and ethical obligations not to disclose classified or confidential information.) That means that the glimpse he is offered is necessarily a skewed one. Add to this the fact that those who talk to Savage are, it seems, largely those at or near the top of the totem pole. Officials who labor day-in-and-day-out on the issues Savage covers — and who have an immensely important role in shaping options and strategies — receive almost no mention. It’s hard to fault Savage for this — he can’t possibly speak to everyone, and he clearly spoke to a huge number of insiders. But it does mean that he has a partial view of how the lawyering process works that doesn’t necessarily reflect the gritty day-to-day reality inside the agencies, where options and rationales are developed by lawyers, many of whom have been at the job for decades.

And, of course, Harold Koh, most pithily (albeit in Savage’s paraphrase), who says it is

easier to take purist stances from the faculty lounge than from a position of responsibility.

All of this bears only one interpretation. For the public and commentators who wonder whether the president is constrained by law, the answer is: “trust us,” the executive-branch lawyers.

“Easier to take purist stances from the faculty lounge than from a position of responsibility”

That’s Charlie Savage paraphrasing Harold Koh in Power Wars. I think this should be carved on the facade of Yale Law School. You can read a glass-half-full review by Jack Goldsmith, and a glass-half-empty review by me. (Or is it the other way around?)

Love your lawyer day: Federal Reserve legal division edition

I ran across this memo from the merry band of pranksters at the Federal Reserve legal division. The memo explains why the Fed could legally buy unsecured commercial paper during the financial crisis–that is, make unsecured loans to businesses–even though under the relevant legal authority the loans must be “secured to the satisfaction” of the Fed.

The lovable lawyers make two arguments. Argument 1 is that the Fed didn’t actually make loans to the businesses. It made loans to a special purpose vehicle that the Fed created. The SPV then turned around and loaned the Fed’s money to the businesses. The Fed’s loan to the SPV was secured by the commercial paper that the SPV acquired from the businesses in return for its (the Fed’s) money.

According to this theory, any unsecured loan to anyone can be converted into a secured loan simply by creating an SPV. You can do it yourself. Just create an SPV, lend money to the SPV, direct the SPV to lend that money to Mr Anyone in return for an IOU from him, and then call the IOU collateral for your loan to the SPV. Voila, an unsecured loan to a person with no assets turns into a secured loan.

Argument 2 is even more clever. The lawyers grudgingly admit that their first argument might be considered specious (they don’t use exactly that word) since as a matter of function the SPV doesn’t do anything at all. So in Argument 2, the lawyers observe that the Fed charges the unsecured CP issuers an “insurance fee” or premium of 1% above the normal interest rate. The “insurance fees” from all the unsecured borrowers are aggregated into an “insurance fund,” which can then pay out to the Fed if any borrower defaults. This insurance fund gives the Fed “security.”

Of course, an unsecured loan always carries a higher interest rate than a secured loan does. That higher interest rate–or call it the “insurance fee” if you want–has precisely the function of protecting the creditor from the extra risk from lending to a borrower who cannot offer collateral. So by the Fed’s logic, any unsecured loan is a secured loan as along as the interest rate for the unsecured loan is higher, as it always is. In short, there is no such thing as an unsecured loan; all unsecured loans are secured.

Happy Love Your Lawyer day!

“We wanted justice but what we got was the Rechtsstaat”

From the NYT.

Bernanke’s memoir

You can buy it here. I found it interesting but also disappointing, for reasons I can’t quite identify. Maybe because:

You can buy it here. I found it interesting but also disappointing, for reasons I can’t quite identify. Maybe because:

- Bernanke extols Fed transparency–which he calls his legacy–but on numerous occasions he mentions cases where he and his colleagues hid their motives, thoughts, and actions. Why? To avoid spooking the market, to retain leverage while bargaining with banks, to allow banks to borrow without being stimgatized, etc. All good reasons, but suggesting that transparency is a more complex ideal than he lets on.

- While Bernanke admits some errors, they are of the minor sort–having to do with leadership and presentation. He refuses to admit the biggest one: the failure to rescue Lehman, which he continues to blame on “the law,” as I note in Slate. So the error-admitting seems more like an exercise in establishing credibility than in admitting error.

- Bernanke mocks the Old Testament types who want to punish financial institutions, but then expresses “anger” at AIG and ensures that it is punished. Which is it?

The most interesting thing I learned, or at least that I infer from the narrative, is that Bernanke wanted above all to ensure that the Fed did not take losses and pass them on to the Treasury. At the same time, he and others have criticized Sheila Bair for taking just such an approach to the FDIC insurance fund rather than focusing on the financial system as a whole. How much of the crisis response was driven by competing bureaucratic mentalities?

The bin Laden raid: where was the OLC?

The Times article describing the legal deliberations prior to the bin Laden raid mentions four lawyers: the CIA’s general counsel; the NSC’s legal adviser; the Joint Chiefs’ legal adviser; and the Pentagon general counsel. All of them, of course, did what executive-branch lawyers do: identify the most convenient legal categories needed for permitting the executive action.

More interesting, the OLC–which would normally be called upon to render the final opinion–was not included. Not just the OLC, but the entire Justice Department was frozen out. Why? Could it be that the OLC was less than cooperative when the White House sought a legal rubber stamp for the Libya intervention in 2011? Has the OLC been demoted for its insubordination?

Is America Heading Toward Dictatorship?

No, I say, in Slate, at least not in the sense that people like Bruce Ackerman or Matthew Yglesias mean. This bold claim puts me in a minority of, maybe, two people.

The Executive Unbound, revisited

Since we published The Executive Unbound: After the Madisonian Republic in 2011,

Since we published The Executive Unbound: After the Madisonian Republic in 2011,

- the President has extended the 2004 AUMF to include ISIS and engaged in a “Forever War” without congressional participation;

- taken military action in Libya, on grounds widely condemned as a transparent circumvention or violation of the War Powers Resolution, while ignoring the contrary views of the Office of Legal Counsel;

- moved aggressively to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, through the EPA, under the authority of a statute enacted in 1970 that says little of relevance, after Congress refused to enact a regulatory scheme for climate change;

- unilaterally announced sweeping immigration enforcement policies that effectively legalized millions of aliens, and that closely tracked the terms of a bill that Congress refused to enact;

- unilaterally delayed rulemaking under the Affordable Care Act, despite unambiguous statutory deadlines, and funded implementation of the Act by diverting appropriations expressly devoted to other purposes;

- missed dozens of statutory deadlines under Dodd-Frank;

- refused to defend the constitutionality of federal statutes, and encouraged their invalidation by the courts;

- used ‘waiver’ authority to dilute or undermine the work participation requirement of the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program;

- used ‘waiver’ authority in No Child Left Behind, which was included in the statute to allow state experimentation, to force states to adopt new education standards not embodied in the law;

- justified recess appointments by a constitutional theory – upheld in principle although not as to particulars by the Supreme Court – that weakens the control of the Senate over the allocation of high offices in government;

- defied an express statutory command, and by so doing obtained, for the first time in the Nation’s history, a Supreme Court decision recognizing exclusive and inherent presidential power to recognize foreign governments;

- refused to enforce federal drug laws against marijuana users in states that legalized marijuana.

“Sovereign is he who decides on the exception.”

— Eric Posner & Adrian Vermeule

What’s the best use for Human Rights Watch’s budget?

For the past few years, I’ve been flogging the idea that money spent to enforce human rights would be more productively devoted to development aid. I make this argument in a book; and I have developed it in an article, just posted on SSRN, which argues that development agencies should not consider themselves constrained by human rights law or required to “promote” human rights, as this idea is sometimes put.

The argument is based on the premise that the “human rights regime” (which is hard to define in any event) does not actually improve the well-being of people in poor (or rich) countries. It’s too hard for outsiders–well-meaning NGOs and more ambiguously motivated governments–to figure out how to advance human rights in foreign countries, or even what that means. There is a huge amount of disagreement about what rights mean and require, and how priorities should be established in a world of limited budgets and attention spans.

A problem with my argument has always been that the same thing can be said about development aid. Although the picture is not as bleak as the human rights picture is, many economists don’t think that development aid does much good. The reasons are similar to the reason why human rights enforcement does not do much good: we (on the outside) often find ourselves flummoxed by foreign cultures, institutions, and values, which overturn the best plans.

Yet here is a paper by David McKenzie that reports the results of a randomized control trial where $36 million was randomly assigned to small businesses in Nigeria that applied for grants in a business-plan competition and reached the semi-final round. The winners received grants of around $50,000. Over the next several years, they hired many more people , innovated more, and earned larger profits than the control group. By stimulating economic activity, the donations did more than just transfer a fixed sum of money to people in a poor country.

Meanwhile, HRW’s budget was $65 million as of 2013. It’s an article of faith that HRW does good, but there is no evidence whatsoever. HRW’s donors should use this paper as an opportunity to exercise effective altruism and redirect their donations accordingly.

What does the collapse of European integration mean for international law?

But the question I want to ask here is what does this chain of crises mean for international law. Back in 2000, law professor Peter Spiro wrote a piece in Foreign Affairs criticizing a tiny gaggle of American international law academics who expressed doubts about what Spiro saw as the inevitable triumph of international legal norms. These “New Sovereigntists” hold thee positions:

The first impugns the content of the emerging international legal order as vague and illegitimately intrusive on domestic affairs. The second condemns the international lawmaking process as unaccountable and its results as unenforceable. Finally, New Sovereigntism assumes that the United States can opt out of international regimes as a matter of power, legal right, and constitutional duty.

While these New Sovereigntists were writing about the United States, not Europe, Europeans might be forgiven for regretting that they never took them seriously. Intrusion on domestic affairs? That’s what Eastern European countries think about refugee policy and the Southern countries about austerity. Unaccountable and unenforceable? That would include laws that were supposed to stop countries from accumulating too much debt and from allowing migrants to travel outside the country of arrival. The happiest countries are those which opted out of the eurozone, and the UK must be feeling pretty pleased that it’s not in the Schengen area. Sovereignty might have slumbered for a few post-Cold War years, but it is returning with a vengeance.

Richard McAdams on Go Set a Watchman

Read this review; it is the best thing written about Harper Lee’s new-old novel. Bottom line:

The 1950s editorial decision not to shepherd a revised Watchman to publication is more questionable than the decision to publish the first draft in 2015. It might not have been as popular as Mockingbird, but it would have been a better novel.

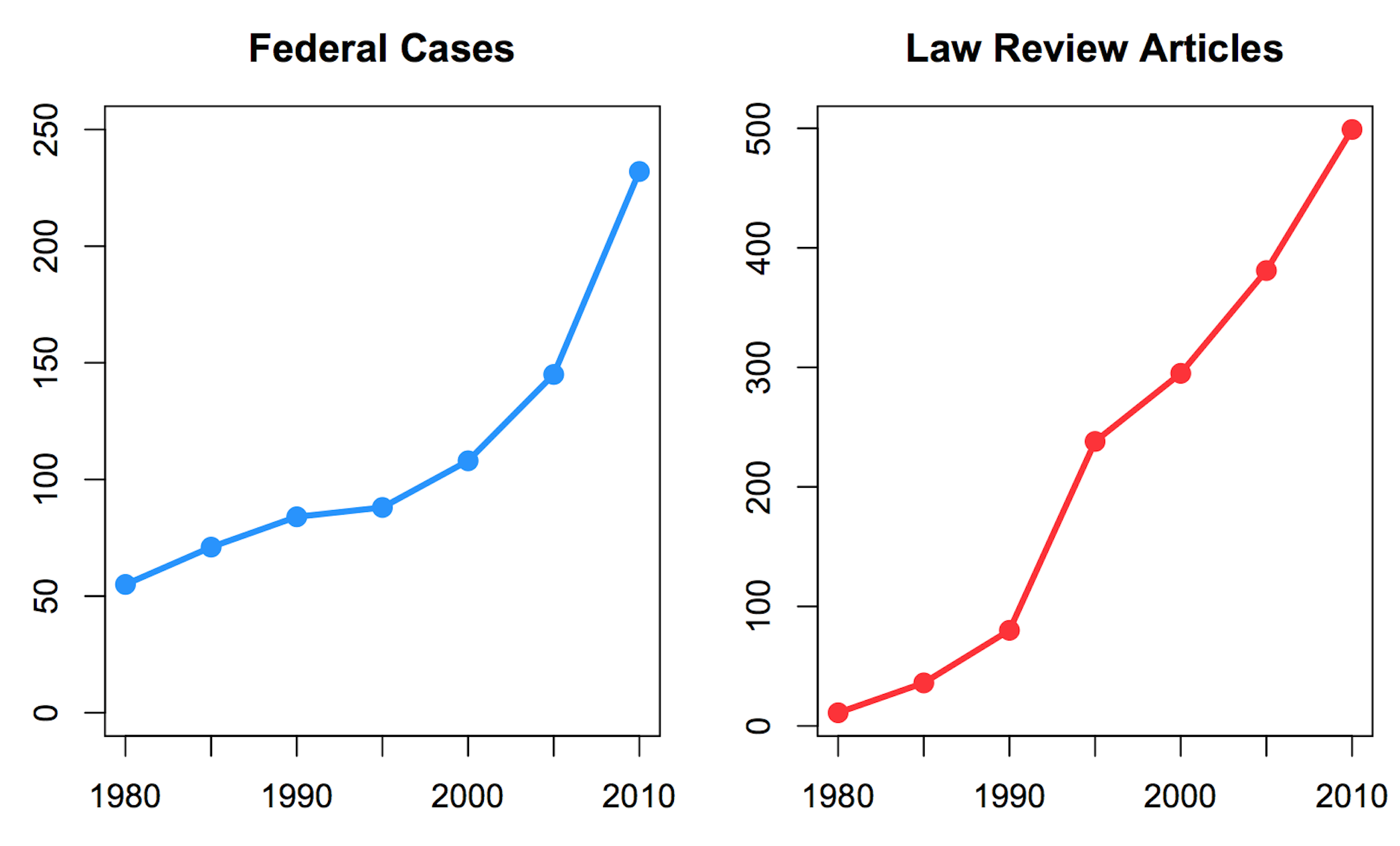

The rise of statistics in law

These graphs show the frequency of the term “statistical significance” or “statistically significant” in judicial opinions and law review articles over time. The graphs should not be surprising and yet they should also be alarming for the legal profession. Few lawyers and hardly any judges have statistical training or more than a rudimentary understanding of statistics. This is all too evident in judicial opinions. Law schools are just beginning to catch up–by hiring people with statistical training–but haven’t figure out a way to give students usable statistical knowledge.

There are some helpful books–most recently, An Introduction to Empirical Legal Research by Lee Epstein and Andrew Martin. We highly recommend it. Holmes said that “For the rational study of the law the blackletter man may be the man of the present, but the man of the future is the man of statistics and the master of economics.” His prediction is finally coming true. But are our students prepared?

— Adam Chilton & Eric Posner

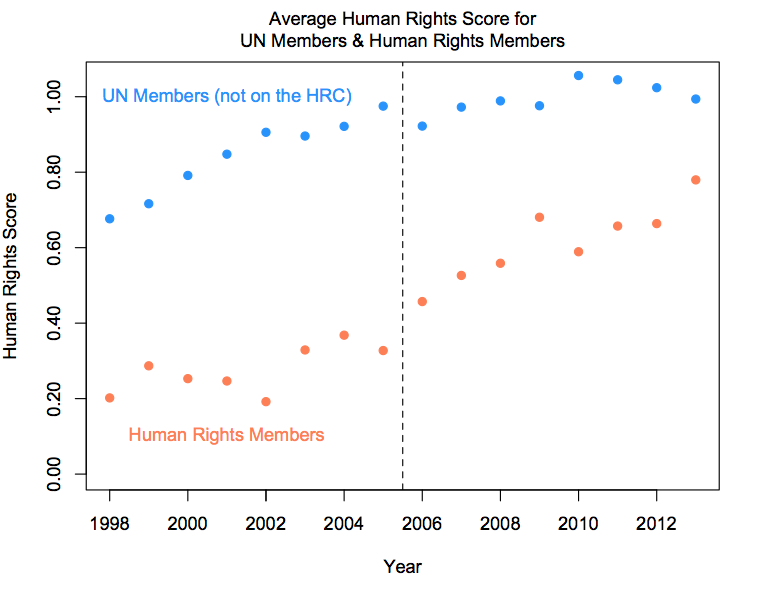

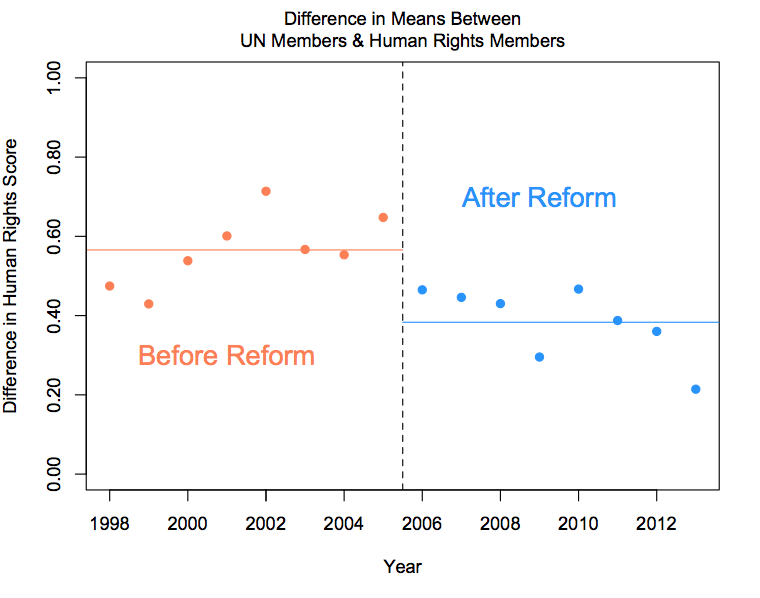

The UN Human Rights Council: “all the cops are criminals…”

Here’s a fun chart, put together by my colleague Adam Chilton. The blue dots show the average human rights performance of all UN members. The red dots show the human rights performance of the members of the special UN human rights body that is supposed to monitor and enforce human rights law. Yes, the members of the human rights body do a lot worse than the average country. Why? Well, it makes sense if you are a human rights violator to lobby for a position on the human rights body, where you can protect yourself from criticism by forming coalitions with other abusers. (The scores for each country are from Chris Fariss’ data set.)

But there is hope for non-skeptics. The UN abolished the much-despised UN Commission on Human Rights and replaced it with the UN Human Rights Council in 2006, and made some effort to improve the membership. As both charts show, the human rights performance of the members increased noticeably. Still, not as good as the average country.

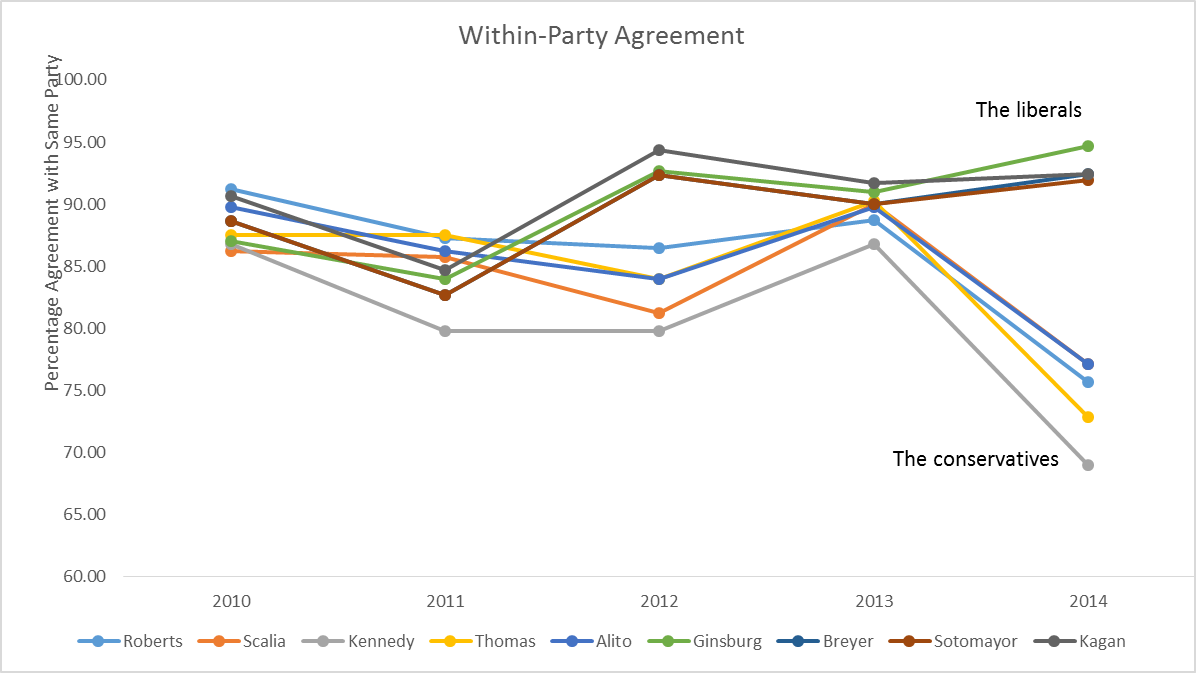

Party and agreement on the supreme court, updated

King v. Burwell and ideological independence

Subject as always to confirmation bias, I’m going to interpret the votes in this case as further support for my argument that the Republican appointees are fragmenting. It’s striking that both Roberts and Kennedy joined the liberals.

See my earlier posts on this topic. What is the explanation? Here are a few (overlapping) possibilities:

1. Kennedy and Roberts are more ideologically moderate than the other Republicans.

2. Roberts is concerned about the legitimacy of the court.

3. Only the Republican appointees take the law seriously, and so are willing to disagree with each other. The Democratic appointees march in lockstep because they care about outcomes.

4. Sunspots; the alignment of the stars; tidal forces.

Partisanship and the supreme court: summary

| Agrees with co-partisans | Disagrees with co-partisans | |

| Agrees with counter-partisans | Bridge-builders: Kennedy, Roberts | Traitors: ∅ |

| Disagrees with counter-partisans | Loyalists: Kagan, Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, Scalia, Alito | Mavericks: Thomas |

Something like this. Perhaps, Justice Stevens could be classified as a traitor (to his party–he was appointed by Nixon Ford but in later years voted with the Democratic appointees–which is not the same thing as saying that he was a bad justice, of course). Among the loyalists, Scalia and Alito vote in a less consistently partisan manner than the other four.

The table is based on my previous posts: here, here, and here.

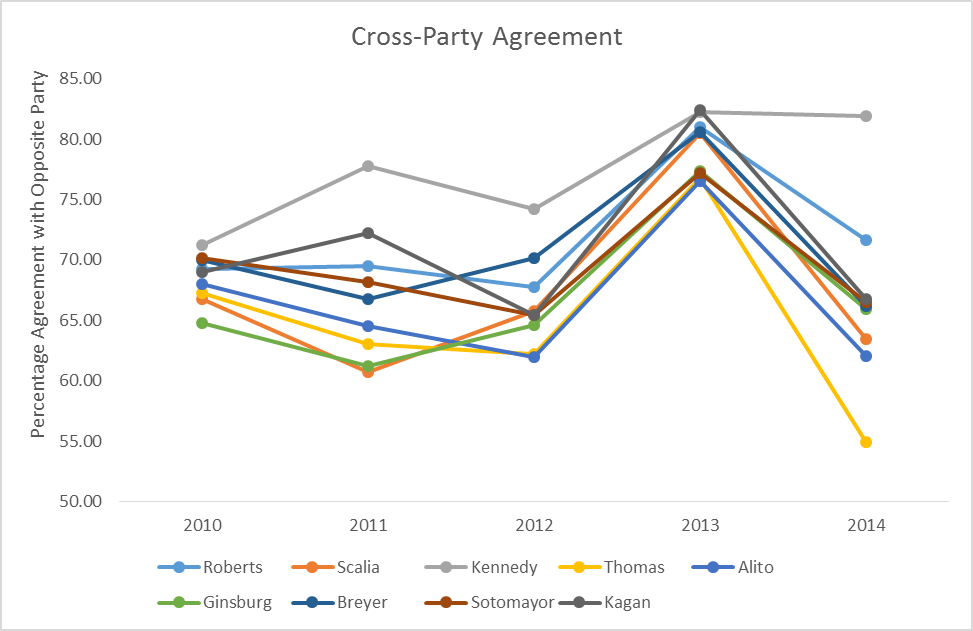

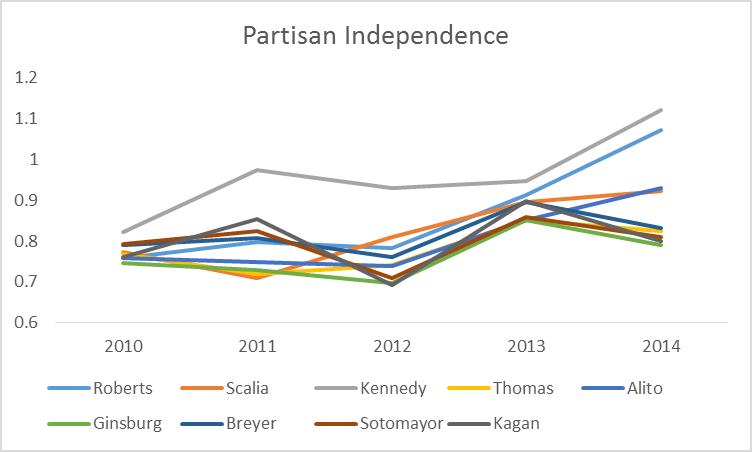

Partisan independence on the supreme court

Define partisan independence as the ratio of cross-party agreement to cross-party disagreement. Partisan independence is highest for those who both frequently disagree with co-partisans and frequently agree with counter-partisans. Kennedy and Roberts lead the pack. In the second group are Scalia and Alito. Thomas now clusters with the Democrats. While Thomas often disagrees with co-partisans, he also often disagrees with counter-partisans–the two tendencies cancel out.

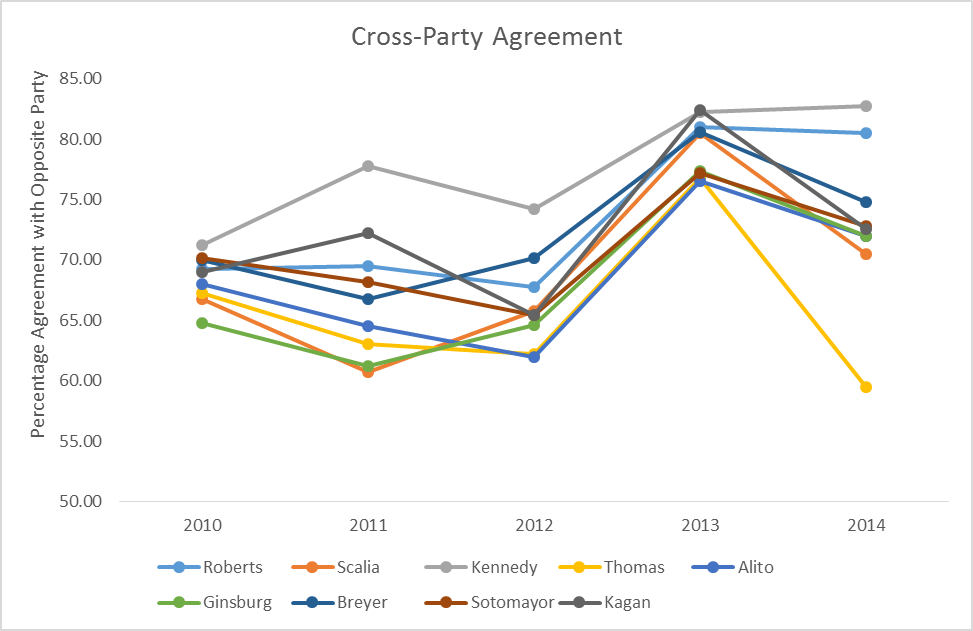

Cross-party agreement in the supreme court

Here is another angle on the relationship between partisan identity and agreement on the supreme court. Three clusters appear. Kennedy and Roberts are most likely to vote with counter-partisans–in their case, the Democratic justices. Thomas (a cluster of one) is least likely to vote with counter-partisans. The remaining justices–the four Democrats, Scalia, and Alito–fall in the middle. As before the 2014 term seems to magnify trends that are perhaps (with the benefit of hindsight) partly discernible in earlier years. Data from Scotusblog.

Here is another angle on the relationship between partisan identity and agreement on the supreme court. Three clusters appear. Kennedy and Roberts are most likely to vote with counter-partisans–in their case, the Democratic justices. Thomas (a cluster of one) is least likely to vote with counter-partisans. The remaining justices–the four Democrats, Scalia, and Alito–fall in the middle. As before the 2014 term seems to magnify trends that are perhaps (with the benefit of hindsight) partly discernible in earlier years. Data from Scotusblog.

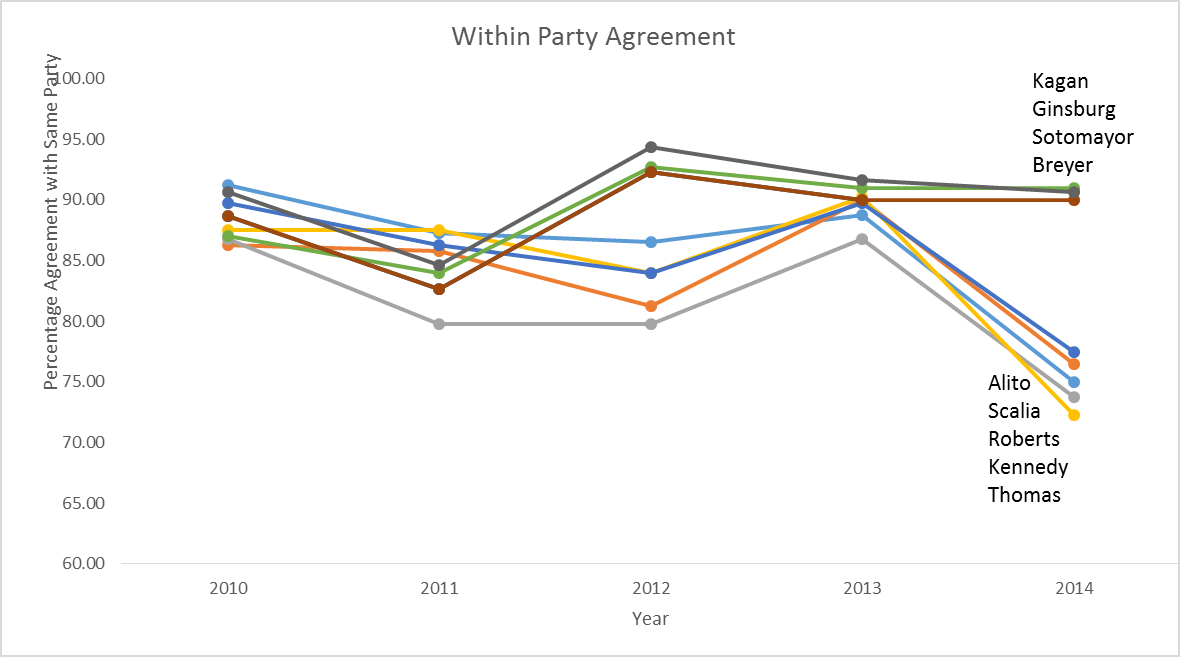

Partisan agreement in the supreme court

This graph shows that Republican-appointed justices disagree among themselves more often than Democrat-appointed justices, who march almost in lockstep. What accounts for the striking acceleration of the trend this year? While some of the most polarizing cases have not yet been decided, I’d be surprised if the final cases make much difference in the pattern. Data source: Scotusblog.

This graph shows that Republican-appointed justices disagree among themselves more often than Democrat-appointed justices, who march almost in lockstep. What accounts for the striking acceleration of the trend this year? While some of the most polarizing cases have not yet been decided, I’d be surprised if the final cases make much difference in the pattern. Data source: Scotusblog.