Here. (Already overtaken by events as Ukraine descends into civil war.)

Category Archives: INTERNATIONAL LAW

Ukraine and the International Criminal Court

Ukraine has asked the ICC to investigate whether the government of President Viktor Yanukovich committed crimes against humanity from November 2013 until the collapse of his government in February. Although Ukraine has not ratified the Rome Statute (and may indeed not be permitted to under its constitutional law), it has take advantage of a provision of that treaty that allows the ICC to investigate crimes in non-member countries that request its aid.

Ukraine should be careful what it wishes for. If the ICC takes the case (which, for various technical reasons, it may not), Ukraine might find itself in a position similar to that of Uganda. Uganda also referred its conflict with a rebel group, the Lord’s Resistance Army, to the ICC, which accepted jurisdiction. But when Uganda tried to settle the conflict under its amnesty law, the ICC refused to withdraw arrest warrants it had issued. Critics now blame the ICC for prolonging the war. Whatever the merits of their criticisms, the Ugandan government is certainly unhappy with the ICC, calling it a tool of imperial powers. For a damning indictment of the ICC’s involvement in Uganda, see this piece by Adam Branch (who also argues that the ICC has helped legitimate Uganda’s repressive government by agreeing to investigate only the rebels).

Similarly, if the ICC gets involved in Ukraine, and issues arrest warrants against Yanukovich and/or his supporters or members of his former government, the Kiev government may be unable to offer terms of settlement that the other side will agree to, while angering the Russians and for that matter everyone who wants to see the conflict end. Here’s betting the ICC will say “thanks but no thanks.”

Anne-Marie Slaughter: How to save Ukraine

First, attack Syria (?):

It is time to change Putin’s calculations, and Syria is the place to do it…. Equally important, shots fired by the US in Syria will echo loudly in Russia. The great irony is that Putin is now seeking to do in Ukraine exactly what Assad has done so successfully: portray a legitimate political opposition as a gang of thugs and terrorists, while relying on provocations and lies to turn non-violent protest into violent attacks that then justify an armed response.

Second, send covert U.S. troops into Ukraine:

Putin may believe, as Western powers have repeatedly told their own citizens, that NATO forces will never risk the possibility of nuclear war by deploying in Ukraine. Perhaps not. But the Russian forces destabilizing eastern Ukraine wear no insignia. Mystery soldiers can fight on both sides.

Why would this work?

Putin … measures himself and his fellow leaders in terms of crude machismo.

Then maybe a hot-pepper eating contest between Putin and Obama would do the trick?

That’s all I can think of to say. Or you could read Robert Golan-Vilella.

Putin’s grand strategy

There has been a lot of loopy speculation about Putin’s motives, much of it based on conjectures about his psychological makeup. Some people think he is irrational. Another view, which is more plausible, is that he acts tactically in response to short-term opportunities but has no strategic vision. But this view is wrong as well. There is a simple, parsimonious explanation for Putin’s actions.

There has been a lot of loopy speculation about Putin’s motives, much of it based on conjectures about his psychological makeup. Some people think he is irrational. Another view, which is more plausible, is that he acts tactically in response to short-term opportunities but has no strategic vision. But this view is wrong as well. There is a simple, parsimonious explanation for Putin’s actions.

Putin sees the United States as a rival, not as a “partner,” and seeks to advance Russia’s interests by ensuring a sphere of influence around the Russian homeland. He has taken advantage of the fact that most of Russia’s neighbors have substantial ethnic Russian populations and, among these countries, most are poor and badly governed, except Estonia and Latvia. This means that Russia can, at low cost and risk, stir up unrest in these countries by encouraging the Russian populations to express separatist ambitions. It follows that countries without significant Russian minorities (like Finland) or are powerful (like China) have little to worry about. Russia today is not the Soviet Union; Poland (a non-neighbor with a tiny Russian population) has nothing to fear.

Putin is not interested in conquering his neighbors, which would be difficult to rule. He just wants them to be in Russia’s orbit. And so his strategy is to punish any neighbor that shows excessive pro-western inclinations by sowing disorder among the Russian speaking population. That is the story of Georgia and Ukraine. Russia would never have bothered annexing Crimea if a pro-Russian government remained in place in Ukraine. Where governments cooperate with Putin (Kazakhstan and Belarus), Putin does not trouble them.

This strategy is a less ambitious version of the Soviet Union’s strategy, and also not much different from what the United States did during the cold war, in places like Cuba and Nicaragua. It’s perfectly logical, and also likely to succeed because a big country cares more about its neighbors than other countries do, and can exert influence over them more easily than other countries can.

The implications for the West are also clear. It needs to decide whether the benefits of attracting Russia’s neighbors into the Western orbit are worth the risks of disorder that result from Russia’s retaliation. The bottom line, I fear, is that places like Georgia, Ukraine, and even Estonia are not important enough, in the long run, for the West to warrant conflict with Russia when Putin can stir up disorder at such little cost to the Russian treasury. Governments in those countries should do everything they can to appease their Russian populations so that they are not responsive to irredentist appeals from the Kremlin.

It seems to me that in the future the biggest problems will be Estonia and Latvia. Both are little countries with big Russian populations. Both are also NATO members, so the West is committed to defending them. Everything should be done to ensure the Russian minorities in those countries will be unresponsive when Putin starts stirring up trouble.

Can Russia oppose U.S. bank sanctions through the WTO?

The Russian government is mulling it over (or pretending to):

“The WTO gives us some additional possibilities,” Ulyukayev was quoted by Interfax as saying on Wednesday. “We at the WTO council in Geneva talked about the possibility of filing lawsuits against the U.S. over the sanctions against Russian banks and we hope to use the mechanism of the WTO to keep our partners in check regarding this issue.”

I know little about this topic so I emailed a colleague who had this to say (I edit slightly):

There is the purely doctrinal question whether the sanctions can be interpreted to contravene some GATS banking commitment by the US respecting market access or non-discrimination. Even if yes, and I do not know the answer, there is still Art. XIV bis on national security exceptions that applies for measures to protect “essential security interests” in “war or other emergency in international relations.” That arguably applies although there is no case law. Add that a WTO case would take three years, by which time all of this is presumably old news anyway.

The broader question of to what extent sanctions can be used under WTO law has received some attention, but is of dubious practical significance. We have embargoed Cuba (a GATT member) for 50 years. No one worried much about GATT during apartheid in South Africa, either.

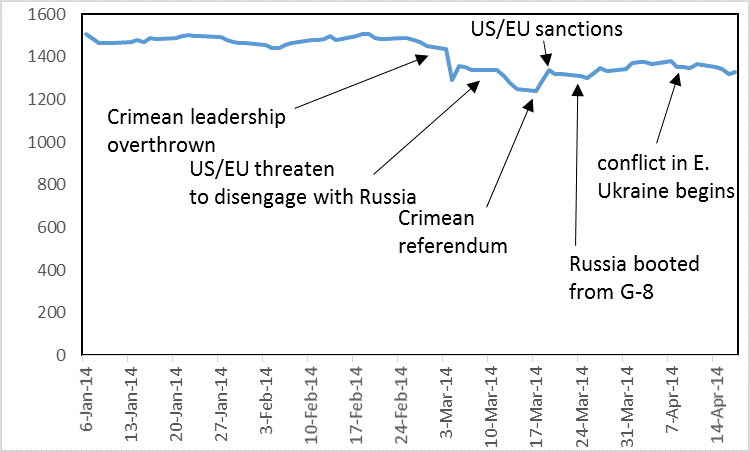

Russian stock prices, Jan.-Apr. 2014

This year is the 105th anniversary of the publication of Norman Angell’s The Great Illusion, which argued that states act against their self-interest by going to war. While its timing was poor (the book was published in 1909), the argument is actually ingenious: Angell argues that if Germany conquered England, it would simply deprive itself of a debtor and trading partner, while obtaining in return only some minerals, the Elgin marbles and a few other treasures, and an unhappy population. Germany would do far better for itself by instead continuing to trade with England.

This year is the 105th anniversary of the publication of Norman Angell’s The Great Illusion, which argued that states act against their self-interest by going to war. While its timing was poor (the book was published in 1909), the argument is actually ingenious: Angell argues that if Germany conquered England, it would simply deprive itself of a debtor and trading partner, while obtaining in return only some minerals, the Elgin marbles and a few other treasures, and an unhappy population. Germany would do far better for itself by instead continuing to trade with England.

People are now making exactly the same argument about Russia. Because the economy of Russia depends on an export market for its oil and on foreign investment, and a few slivers of Ukraine will most likely be a burden rather than a benefit, Russia’s self-interest should direct it to leash the dogs of war. But the graph above suggests that there is less at stake for the Russian economy than might first appear.

The “civil war” in Ukraine

From Bloomberg:

“Blood was spilled once again in Ukraine,” Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev said on Facebook today. “There’s a sense in the country that a civil war could break out.” Putin “is getting many requests” from eastern Ukraine “to intervene in one way or another,” his spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, told reporters yesterday.

It’s significant that Medvedev invokes “civil war.” No civil war exists in Ukraine–there is a bit of unrest, possibly a near-insurgency. But if a civil war did exist, it would help pave the way for a Russian intervention. Strictly speaking, foreign countries are supposed to stay out of civil wars under international law. But, in practice, they never do. If Russia does intervene, Putin will be sure to cite U.S. involvement on the side of the rebels in the Syrian civil war. An even better precedent is U.S. aid to the Contras in Nicaragua in the 1980s, where the U.S. played a facilitating role similar to Russia’s in Ukraine.

Still, if and when a civil war breaks out, it will break out in large part because of Russian encouragement and indeed leadership, so we will need to put into the category of “hubris” any future Russian argument that it must intervene because a civil war has broken out in a neighboring country. Yet if that happens, it will increase Russia’s bargaining power with the west, because Russia is in the best position to broker, monitor, and enforce a peace agreement between Kiev and the “rebels.”

Chutzpah award, Ukraine edition

Alexei Miller, the head of Gazprom, has explained that the reason for raising gas prices for Ukraine is in part that Ukraine no longer is entitled to discounts that it received in return for leasing the Black Sea fleet base. According to Bloomberg:

In Kharkiv in 2010, Ukraine agreed to extend Russia’s lease to the Black Sea Fleet base in Crimea from 2017 to 2042 in exchange for cheaper gas. Russia has no need for the accords after the peninsula’s accession, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev said last month, calling for Ukraine to pay about $11 billion lost to Russia’s budget.

Of course, the lease is void because Russia now owns Crimea! The original purpose of the contract has been frustrated, as a contract lawyer would say. You can’t lease property from yourself. But shouldn’t Russia compensate Ukraine for the loss of a chunk of its territory, if we’re going to be legalistic about this? (Miller’s better argument is that Ukraine forfeited its discount by failing to pay prior debts.)

Joseph Blocher and Mitu Gulati argue that Putin should have bought Crimea rather than taken it:

Perhaps if Mr Putin had negotiated to buy Crimea instead of taking it over, Ukraine could have negotiated for both debt relief and multiple years of cheap gas in exchange. Russia might even have helped the current Ukrainian government track down some of the funds that the members of the prior government supposedly absconded with. On the flip side, there would not have been any need for all the chest beating, troop movements, and so on. And the international community surely would’ve been more likely to bless the result—a result for which Russia might be willing to pay some premium.

But why pay for something that you can take for free? Anyway, the chest beating seems to have been the major benefit for Putin. And if a sale was really in everyone’s interest, there is nothing in international law that would have blocked it.

The IPCC report and climate justice

As the magnitude of the harms from climate change becomes clearer, poor countries have redoubled their efforts to achieve “climate justice”–large sums of money from rich countries, at least $100 billion, to compensate them for the harm caused by climate change. As the New York Times puts it,

As the magnitude of the harms from climate change becomes clearer, poor countries have redoubled their efforts to achieve “climate justice”–large sums of money from rich countries, at least $100 billion, to compensate them for the harm caused by climate change. As the New York Times puts it,

Countries like Bangladesh and several in sub-Saharan Africa that are the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change say the report strengthens their demand for “climate justice” — in other words, money, and plenty of it — from the world’s richest economies and corporations, which they blame for the problem.

But there’s a problem: President Obama and Secretary of State Kerry

know there is no chance that a Congress focused on cutting domestic spending and jump-starting the economy will enact legislation agreeing to a huge increase in so-called climate aid. Since 2010, the Obama administration has spent about $2.5 billion a year to help foreign countries adapt to climate change and adopt low-carbon energy technology.

It will be a stretch even to continue that level of spending.

And not just for the United States. Other developed countries are also not likely to give much aid to poor countries.

So what’s to be done? The answer is pretty clear: countries will need to negotiate a climate treaty that does not redistribute wealth from rich countries to poor countries. You can have a climate treaty, but you can’t have climate justice, and the sooner everyone realizes this, the sooner a treaty will be negotiated.

I have made this argument (at greater length) in several places, including this book, this article, and this column.

Koskenniemi on human rights

I have posted at SSRN a short paper on Martti Koskenniemi and human rights, written for an edited volume on his work. Koskenniemi is a distinguished Finnish international law scholar who has argued in several books that international law is indeterminate, and so tends to get harnessed to various political agendas even while its practitioners claim that international law is “neutral.” Koskenniemi focuses on the rhetoric of international legal scholarship; in my paper, I link his indeterminacy arguments about human rights law to the practices of states. If Koskenniemi is right, it would be surprising if states obeyed international human rights law, wouldn’t it?

Is Ukraine doomed?

I mean doomed to lose its autonomy as a nation-state, whether or not its borders remain formally in place. Here are some reasons for thinking that it is:

1. Russia has placed 40,000 troops along its borders. The West has made clear that Ukraine is not worth a war. In the president’s words:

Of course, Ukraine is not a member of NATO, in part because of its close and complex history with Russia. Nor will Russia be dislodged from Crimea or deterred from further escalation by military force.

2. NATO is “suspending cooperation” with Russia, meaning:

Russia could not participate in joint exercises such as one planned for May on rescuing a stranded submarine, a NATO official said.

But, never mind–

Russia’s cooperation with NATO in Afghanistan – on training counter-narcotics personnel, maintenance of Afghan air force helicopters and a transit route out of the war-torn country – [will] continue.

3. Ukraine is deeply in debt to Russia among other countries, and is on the brink of economic ruin. Russia has just increased natural gas prices for Ukraine from $268.50 per 1,000 cubic meters to $385.50.

4. The $18 billion IMF package will help Ukraine pay its debts to Russia, and pay for gas from Russia, at the newly high prices. Think of the IMF package as a subsidy to Russia that counteracts the picayune sanctions.

5. Russia has announced an economic development plan for Crimea that ethnic Russians in eastern Ukraine will look at with envy.

6. Ukraine is deeply divided between East and West. Russia has argued that Ukraine should be given a “federalist” structure, and this proposal may be sensible. As Ilya Somin explains:

Federalism has often been a successful strategy for reducing ethnic conflict in divided societies. Cases like Switzerland, Belgium, and Canada are good examples. Given the deep division in Ukrainian society between ethnic Russians and russified Ukrainians on the one hand and more nationalistic Ukrainians on the other, a federal solution might help reduce conflict there as well by assuring each group that they will retain a measure of autonomy and political influence even if the other one has a majority in the central government. Although Ukraine has a degree of regional autonomy already, it could potentially would work better and promote ethnic reconciliation more effectively if it were more decentralized, as some Ukrainians have long advocated.

But it is predictable that a federal system in which Ukraine effectively consists of two regions–a Ukrainian region and a Russian region–will produce a weak country whose eastern half is dominated by Russia and whose western half will be isolated and alone.

7. Most important, Ukraine has never shown itself able to exist as a viable independent nation. Throughout nearly all of its history, it has been a province of Russia, or divided between Russia and other neighbors. The major period of independence from 1991 to the present–a blink of an eye–has been marked by extreme government mismanagement that has resulted in the impoverishment of Ukrainians relative to Poles, Russians, and other neighbors. In the 1990s, many experts doubted that Ukraine would survive. Now that Russia is back on its feet, their doubts seem increasingly realistic.

Russia has considerable leverage; it will use it.

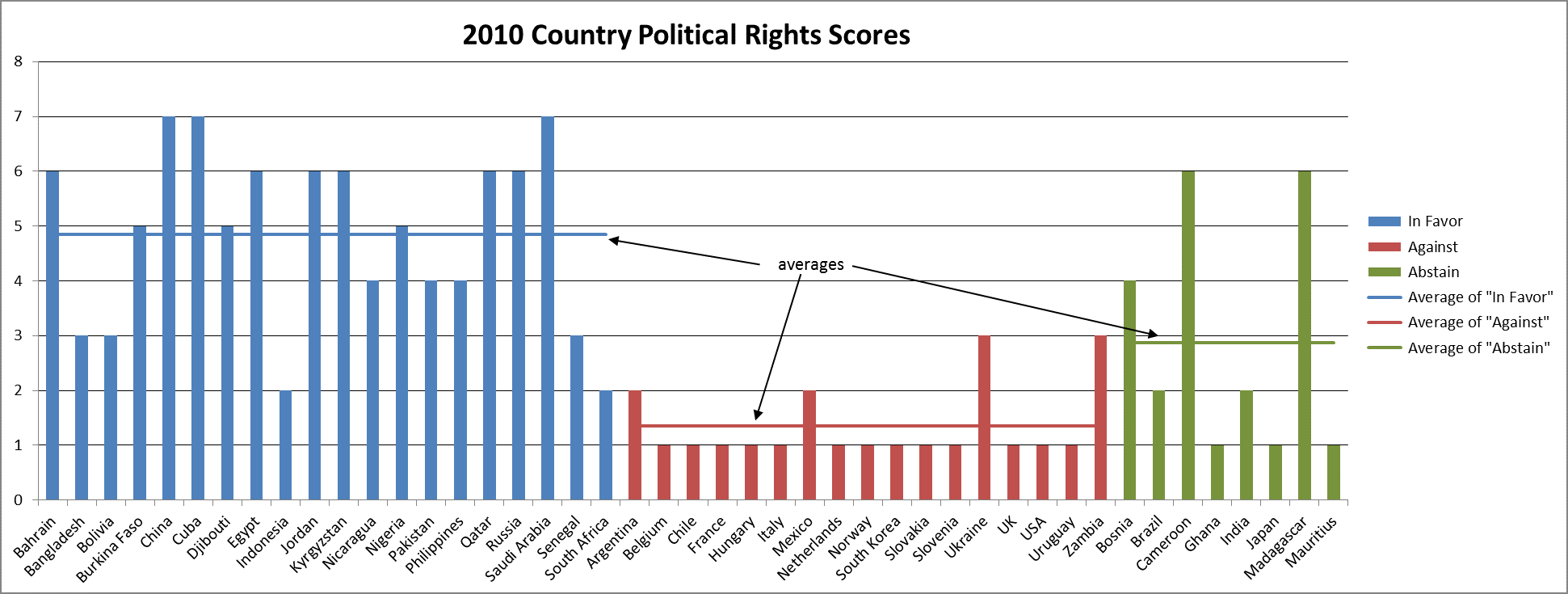

The Human Rights Council and defamation of religion

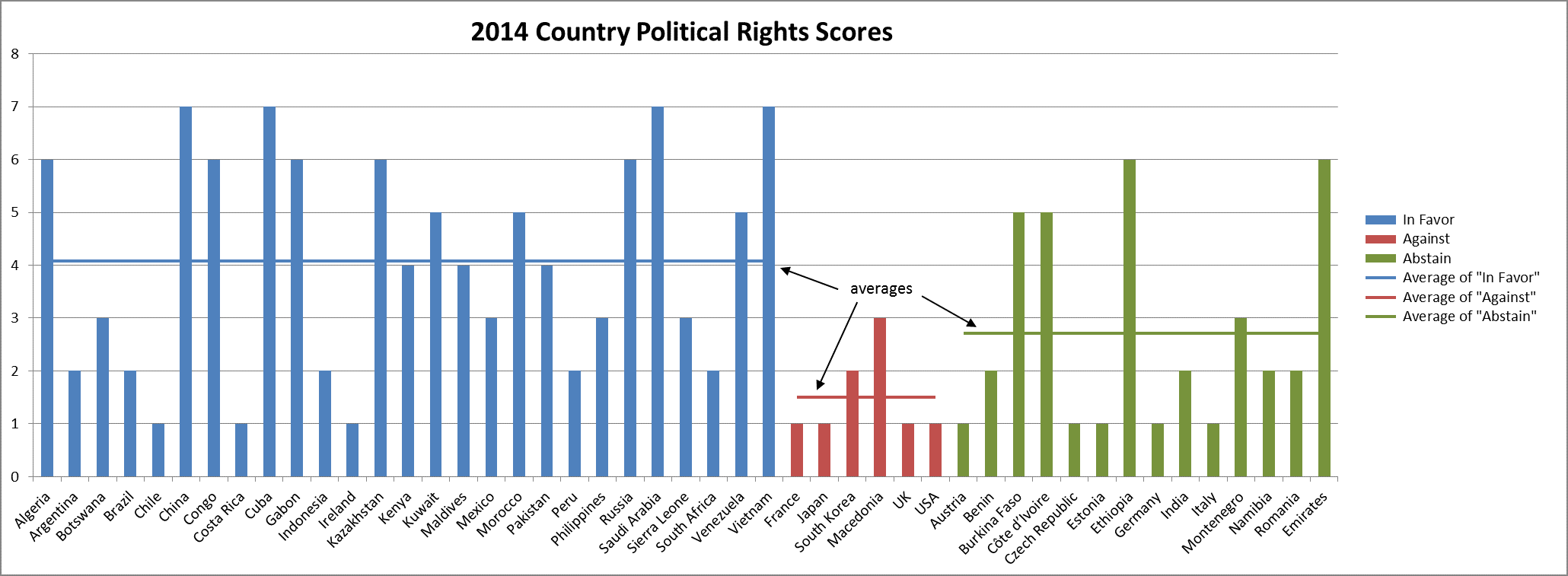

Yesterday I claimed that governments do not take the Human Rights Council seriously. The most famous example is the effort by that body to advance a right against “defamation of religion.” In 2010, a resolution supporting this right was passed by a vote of 20 to 17 with 8 abstentions. (There have been other votes in favor as well, both in the Human Rights Council and the General Assembly.) The graph showing the breakdown of votes by Freedom House score is above. The question for international lawyers is whether western governments like that of the United States are required to recognize a right against defamation of religion because a bunch of authoritarian countries think it should. If not, how exactly should we understand the legal status of the Human Rights Council?

Yesterday I claimed that governments do not take the Human Rights Council seriously. The most famous example is the effort by that body to advance a right against “defamation of religion.” In 2010, a resolution supporting this right was passed by a vote of 20 to 17 with 8 abstentions. (There have been other votes in favor as well, both in the Human Rights Council and the General Assembly.) The graph showing the breakdown of votes by Freedom House score is above. The question for international lawyers is whether western governments like that of the United States are required to recognize a right against defamation of religion because a bunch of authoritarian countries think it should. If not, how exactly should we understand the legal status of the Human Rights Council?

The Human Rights Council and the role of authoritarian countries

Last week the UN Human Rights Council approved a resolution that requires states

Last week the UN Human Rights Council approved a resolution that requires states

to ensure transparency in their records on the use of remotely piloted aircraft or armed drones and to conduct prompt, independent and impartial investigations whenever there are indications of a violation to international law caused by their use.

Ryan Goodman discusses the implications of this vote for international law. My view is that it has no implications. The views of the Human Rights Council are rarely taken seriously by governments. To see why, click on the graph pasted above. It reflects a pattern in votes of this type: that the apparently “progressive” resolution is in fact supported by (mainly) authoritarian countries like China and Saudi Arabia, while opposed by liberal democracies. Freedom House ranks countries based on their political rights from 1 (best) to 7 (worst). The average score of the resolution’s backers (the blue bars in the graph) is 4.1, while the resolution’s opponents (red) average 1.5, and the abstainers (green) average 2.7.

Anyone who thinks that resolutions like this one reflect a conscientious effort to interpret international human rights law doesn’t understand how the Human Rights Council operates. I will provide another example tomorrow.

Crimea, sanctions, and secession

In Slate I argue (once more) that the West can’t do much about Crimea. This time I focus on the ineffectiveness of economic sanctions against a large country, and I touch on the question of whether, and how much, the annexation harms western interests or principles. In short, the costs of sanctions are high and the benefits low. If Russia invades the rest of Ukraine, the calculus may change.

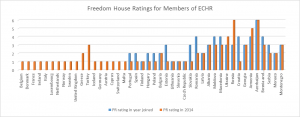

The European Court of Human Rights and Freedom House Ratings

This graph (you may need to squint) shows Freedom House political rights scores for countries that belong to the European Court of Human Rights. The blue bar shows their score at the time of accession (if a FH score is available; they go back only to the 1970s), and the orange bar shows the score in 2014. I was curious about how countries have fared in light of Russian and Turkish backsliding, and of a general sense that international human rights is stagnating, but most countries have improved or not changed. A score of 1 is best; 7 is worst. Note that countries are arranged in the order that they joined the Council of Europe; the original members joined in 1949; Portugal in 1976; and Montenegro in 2007.

Jeffrey Sachs on the “crisis of international law”

Sachs argues that there is a crisis in international law, based not only on Russia’s actions in Crimea but on the general disregard of use of forces rules by the United States and other western countries:

As frightening as the Ukraine crisis is, the more general disregard of international law in recent years must not be overlooked. Without diminishing the seriousness of Russia’s recent actions, we should note that they come in the context of repeated violations of international law by the US, the EU, and NATO. Every such violation undermines the fragile edifice of international law, and risks throwing the world into a lawless war of all against all.

Sachs’ argument raises a number of questions:

(1) Is there a crisis in international law? And if so, did it start with Russia’s intervention in Crimea (as some people might argue), or earlier with U.S. and European actions going back 10-15 years?

(2) Sachs traces the crisis back to the 1999 Kosovo intervention. But the sorts of illegal uses of forces he describe go back very far, for example, the 1989 intervention in Panama, or the 1983 intervention in Grenada, or the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. There is a sense in which the use of force rules have been in crisis since their (modern inception) in the UN charter in 1945. Why draw the line at 1999?

(3) Sachs implies that western illegality paved the path to Russia’s violation of international law. Is it true that if (for example) NATO had not illegally intervened in Kosovo or Iraq, then Russia would not have illegally intervened in Crimea? Is international law a “fragile edifice” that can be undermined by violations, or do the violations just tell us that existing rules are not well tailored to states’ interests? What of the argument that the Kosovo intervention, while illegal, stopped an even worse form of illegality, the ethnic cleansing of thousands of civilians?

(4) What does it mean for international law to be “in crisis”? That it is ignored? A better definition might be that states hold onto the law, they refuse to declare it defunct and try to rationalize their actions as legal, but they frequently violate it. A crisis exists not just because the rules are violated but because states can’t agree on a set of rules to replace them, generating uncertainty and misaligned expectations that could lead to war.

Sachs concludes that the United States should turn to the Security Council to address the Crimea crisis. But note the paradox: Because Russia enjoys the veto, it can immunize itself from Security Council action, and thus continue to violate international law without facing a (formal) legal sanction. The route to peace might circumvent the Security Council. It may be that you can have law or peace, but not both.

Should Ukraine have kept its nuclear weapons?

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine inherited a huge nuclear arsenal, which it subsequently gave up. In return it received assurances from Russia, the United States, and the United Kingdom that its territorial integrity would be respected. These assurances were embodied in the Budapest Memorandum of 1994. While the United States and the UK complied with that agreement by not invading Ukraine, Russia did not.

What if Ukraine had retained its nuclear arsenal? It seems more than likely that Russia would not have invaded Crimea. Putin might have calculated that Ukraine would not have used its nuclear weapons in defense because then Ukraine would itself have surely been obliterated by Russia. But the risk of nuclear war would have been too great; Putin would have stayed his hand. (However, it is possible that Ukraine would have been forced to give up its nuclear weapons one way or the other long before 2014.)

So between meaningless paper security assurances and nuclear weapons, the latter provides a bit more security. One implication of the Crimea crisis may be the further unraveling of the nuclear nonproliferation efforts that President Obama has made the centerpiece of his foreign policy.

My non-testimony at the PCLOB

Last week, I was supposed to testify before the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board, but wasn’t able to because of a flight delay. My written statement is here. My panel was asked to answer two questions.

1. Does International Law Prohibit the U.S. Government from Monitoring Foreign Citizens in Foreign Countries?

I said “no.” The U.S. government has long taken the position that the relevant treaty–the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which includes a right to privacy–does not apply to conduct abroad, based on article 2(1), which says “Each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to respect and to ensure to all individuals within its territory and subject to its jurisdiction the rights recognized in the present Covenant.” Some NGOs and other countries disagree, but even if they’re right, it’s hard to imagine that surveillance targets like foreign citizens or government officials, fall within U.S. “jurisdiction.” And then the ICCPR doesn’t define “privacy,” and the treaty has never been understood to block monitoring of this type, as far as I know. That is why the Germans have recently proposed a new treaty, an optional protocol to the ICCPR, that would limit surveillance.

2. Should the United States Afford All Persons, Regardless of Nationality, a Common Baseline Level of Privacy Protection?

“No” again. Why should it? No other country that has the capacity to engage in surveillance respects the privacy of Americans. If nothing else, read this statement by Christopher Wolf, who describes the foreign surveillance laws and policies of other countries. Here is an excerpt about French law:

The 1991 [French] law is comparable to FISA in that it provides the government with broad authority to acquire data for national security reasons. Unlike FISA, however, the French law does not involve a court in the process; instead, it only involves an independent committee that only can recommend modifications to the Prime Minister. In addition, France’s 1991 law is broader than FISA in that it permits interceptions to protect France’s “economic and scientific potential,” a justification that is lacking in FISA.

The Kosovo precedent

There are actually two Kosovo precedents: (1) the 1999 war, and (2) the 2008 declaration of independence. Putin cites both–the first for the military intervention in Crimea, the second for the subsequent secession/annexation of Crimea.

Focusing on the first, much of the debate has turned on whether Crimea is like Kosovo, with western critics arguing that the Kosovo intervention was justified by humanitarian considerations not present in Crimea. The problem with this argument–if understood as a legal argument–is that no one believes that the Kosovo intervention was legal. The U.S. government has not made such a claim. Here is an account from a state department lawyer named Michael Matheson:

NATO decided that its justification for military action would be based on the unique combination of a number of factors that presented itself in Kosovo, without enunciating a new doctrine or theory. These particular factors included: the failure of the FRY to comply with Security Council demands under Chapter VII; the danger of a humanitarian disaster in Kosovo; the inability of the Council to make a clear decision adequate to deal with that disaster: and the serious threat to peace and security in the region posed by Serb actions.

This was a pragmatic justification designed to provide a basis for moving forward without establishing new doctrines or precedents that might trouble individual NATO members or later haunt the Alliance if misused by others. As soon as NATO’s military objectives were attained, the Alliance quickly moved back under the authority of the Security Council. This process was not entirely satisfying to all legal scholars, but I believe it did bring the Alliance to a position that met our common policy objectives without courting unnecessary trouble for the future.

Matheson could have argued that the UN Charter’s flat ban on the use of military force should be interpreted away, perhaps in light of the Charter’s reference to human rights or some such thing. The UK would make such an argument. The U.S. never did. It still does not. The translation of Matheson’s exquisitely tortured statement is that we broke the law; we won’t do it again; and you better not, either.

Putin may be forgiven his skepticism about the “we won’t do it again” claim. The U.S. would do it again in 2003 (Iraq) and (arguably) 2011 (Libya). It did it before in 1989 (Panama) and 1983 (Grenada). Jack Goldsmith says, plausibly, “International law drops out because both actions were illegal, leaving only a fight over ‘legitimacy,’ which is even more in the eye of the beholder than legality.”

We can go farther. The U.S. did not advance a humanitarian intervention exception to the ban on the use of force because it did not believe that such an exception served its interests. It would open the door to other countries intervening whenever they believed humanitarian considerations justified intervention, leading to a surely impossible debate about what conditions constitute a humanitarian emergency and depriving the Security Council veto of its value. Russia and China also rejected the humanitarian intervention exception. So it could never become a part of international law.

Can the United States nonetheless argue that, while it broke the law in Kosovo and never paid a penalty, now, henceforth, it and everyone else must follow it? The problem with this argument is that the current use of force rules embodied in the UN charter can be mutually acceptable to all countries only in fact if all countries follow them. If only the United States can break them by citing “pragmatic” considerations, the United States alone possesses a veto. Russia, China, and the rest need to decide whether Kosovo was a one-off event or not. They appear quite rationally to have concluded that it was not one-off, and that the United States doesn’t take seriously the UN rules. And so they will not, either.