Guest post by Martin C. Schmalz, University of Michigan.

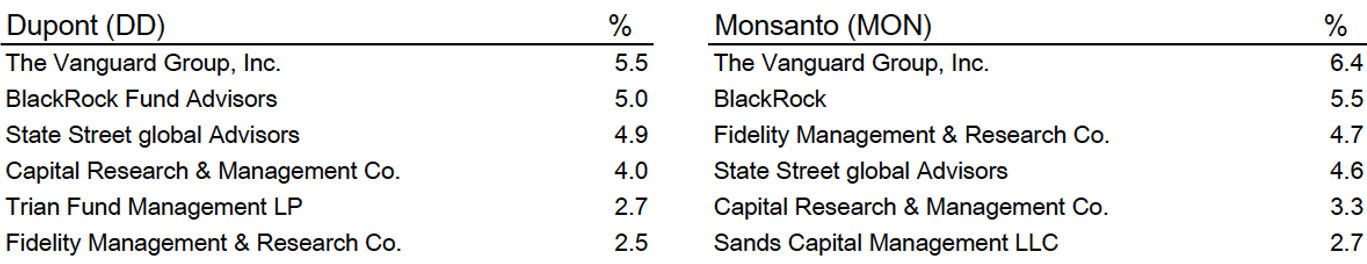

Last week, Nelson Peltz’s hedge fund Trian lost a proxy fight at DuPont. The outcome of the battle received much attention, among others because the “passive” investors Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street were instrumental in making his bid fail – they voted against him. Commentators have ex-post rationalized the failure of the campaign with gaps in some of Peltz’s arguments, his personality, and other factors. Curiously, nobody seems to have taken a look at how Peltz’s and the “passive” funds’ economic incentives differed. This note takes a first look at those, and comes to rather interesting conclusions.

According to Trian’s presentation filed with the SEC, the primary goal of Peltz’s campaign was to help DuPont achieve “best in class revenue growth.” He points out that DuPont’s performance in recent years was satisfactory only because of a positive industry-wide trend, but not if measured relative to DuPont’s competitors. Note for later that the first peer mentioned for comparison in the presentation is Monsanto. A second point of critique concerned DuPont’s lack of aggressive investment in R&D and other measures to gain market share. Third, Trian criticizes DuPont’s CEO for selling a large fraction of her shares in DuPont under the tenure of the index funds, a move that weakened her incentives to make DuPont perform well as an individual firm and strengthen the firm’s relative competitive position. Fourth, Peltz criticizes that DuPont willingly violated a Monsanto patent, then chose to pay $750m more than required in a settlement, and entered a licensing agreement with Monsanto until 2023, effectively pre-committing future cash flows to the competitor. Peltz also criticizes DuPont for “paying competitors” for such licenses more generally.

Peltz’s arguments make perfect sense according to the conceived wisdom reflected in corporate finance textbooks, which assume that all shareholders are undiversified: Peltz’s motion for an increased use of relative performance evaluation, for steeper CEO incentives and against wealth transfers to competitors at the expense of DuPont’s shareholders – textbooks would consider all of these measures value-enhancing improvements of DuPont’s corporate governance. Also, Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), a proxy advisory firm, supported Peltz’s campaign.

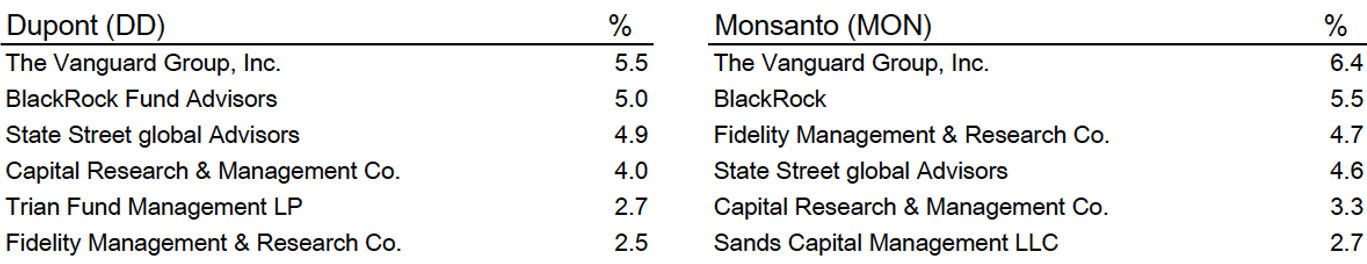

As we know since last week, these arguments left DuPont’s largest shareholders – the diversified investors Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street – unimpressed. They voted against Peltz, leading to a rejection of his bid, and a multi-billion dollar drop in DuPont’s stock price (indicating the market also thought DuPont would have been more valuable with Peltz on the board). So why did the mutual funds not share Trian’s goals?

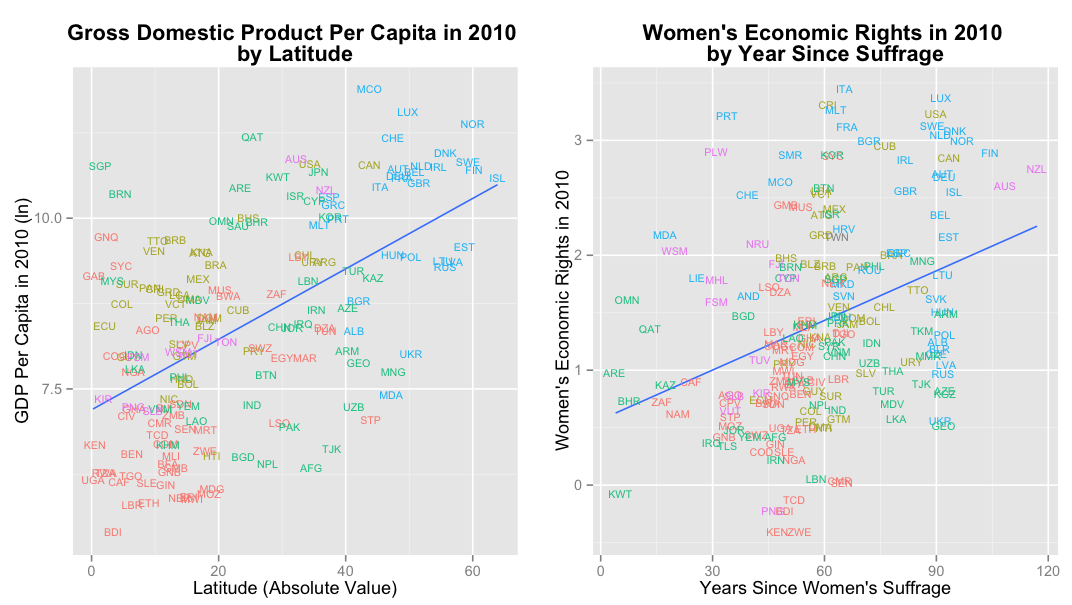

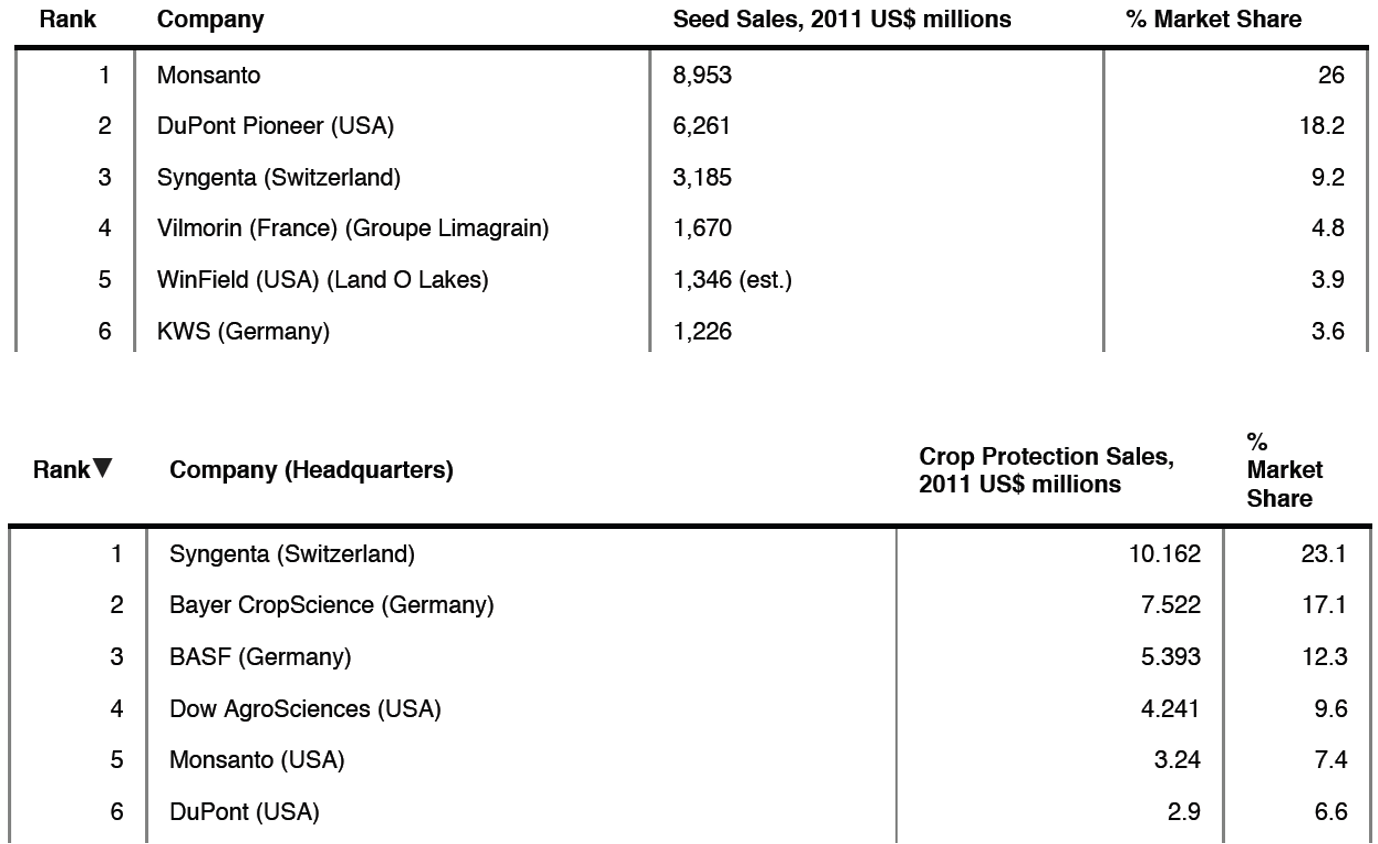

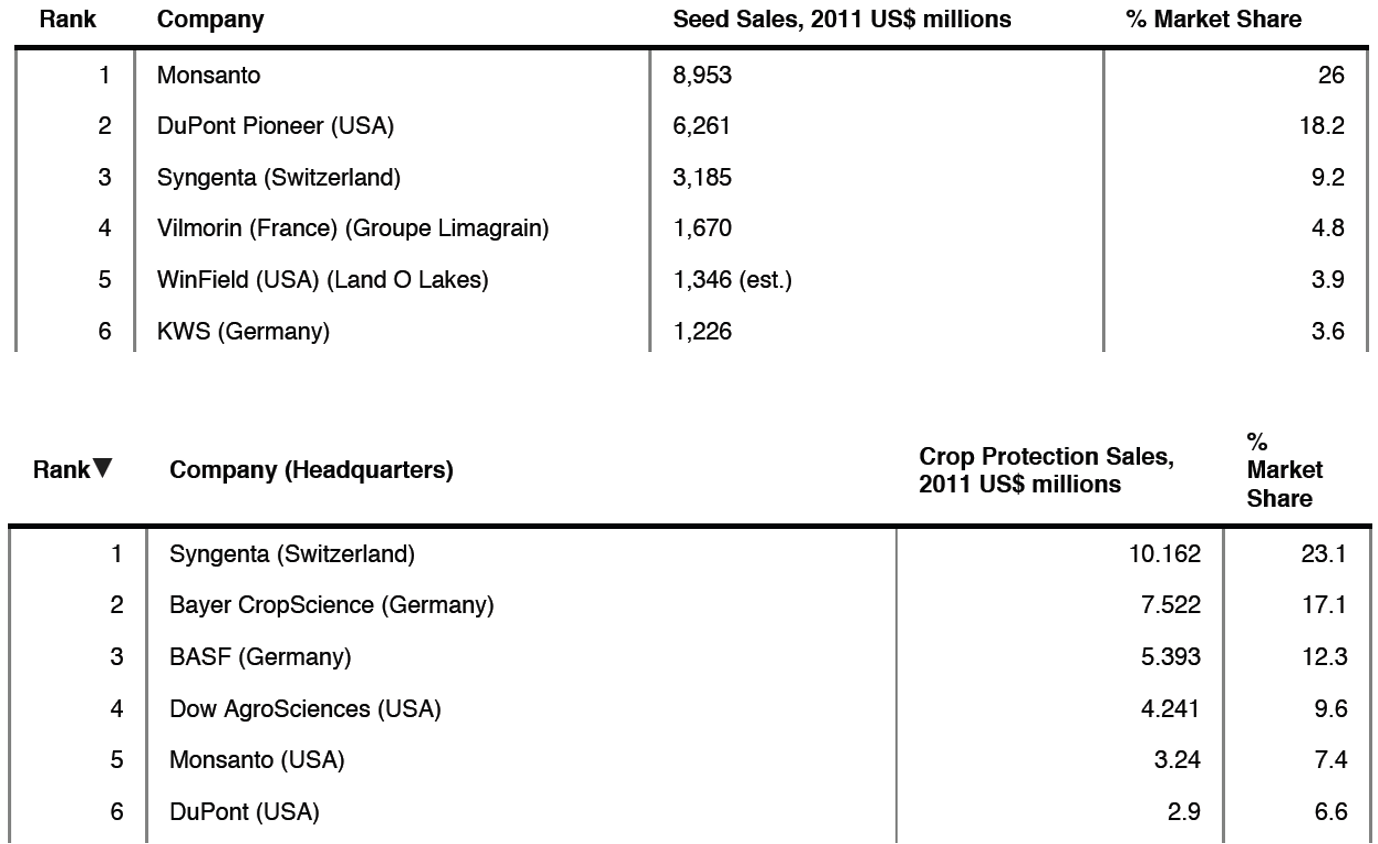

To answer that question, it is instructive to see who DuPont’s competitors are. A quick browse gives a first indication why Peltz considers Monsanto to be DuPont’s primary competitor: Monsanto and DuPont are the two firms dominating the seeds market, and Monsanto is DuPont’s next-largest competitor in the fertilizer and pesticides market. Conversely, these two markets generate almost all of Monsanto’s revenue.[1]

Peltz believes competing harder would increase DuPont’s value. For example, DuPont could decrease prices in the seeds market, and thus increase its market share. The stock market, as indicated by the stock price reaction amid the news of Peltz’s failed bid, appears to agree. The lower market prices for seeds would also lead to greater output and ultimately lower product prices for consumers – for short, greater economic efficiency. However, it would hurt Monsanto’s shareholders if DuPont were to compete more aggressively: DuPont’s increase in market share would come at the expense of Monsanto’s. So who are Monsanto’s shareholders?

It turns out that the same “passive” funds that helped reject Peltz’s bid at DuPont are – in the same order – also the dominant shareholders of Monsanto. In fact, with the exception of Peltz’s Trian Fund, the two firms’ top shareholders are almost identical.

The “passive” funds have no reason to object against cash transfers from DuPont to Monsanto – it’s just a transfer from one pocket to the other. Of course, Peltz (and everyone else who has a sufficiently steep interest in DuPont’s value) should object. That is the first source of imperfectly aligned incentives between the passive funds and Trian.

The more important insight, however, is that the common shareholders of the two firms would suffer from increased competition. Because prices would be lower, so would be the combined revenue and profits of DuPont and Monsanto. That outcome is in strict discord with the economic interests of Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street. That is the second – and socially important – source of disagreement between the economic interests of Trian and the mighty mutual funds.

Here is one last nugget. Guess which company among DuPont’s competitors experienced a major change in stock price while DuPont’s price dropped in response to the news that Peltz’s bid failed. From market close on Tuesday to opening on Thursday, Monsanto’s shares gained 3.5%.

It appears that a dispassionate look at different shareholders’ economic incentives supplies a rather simple rationale for why the passive funds did not themselves enforce relative performance evaluation, protest the weakening of DuPont’s CEO’s incentives, encourage more R&D and gains in market share, and so forth.[2] Doing so simply isn’t in their economic interest. Peltz’s campaign, by contrast, aimed at increasing DuPont’s value in isolation, by strengthening DuPont’s relative competitive position. Predictably, the mutual funds voted against him.[3]

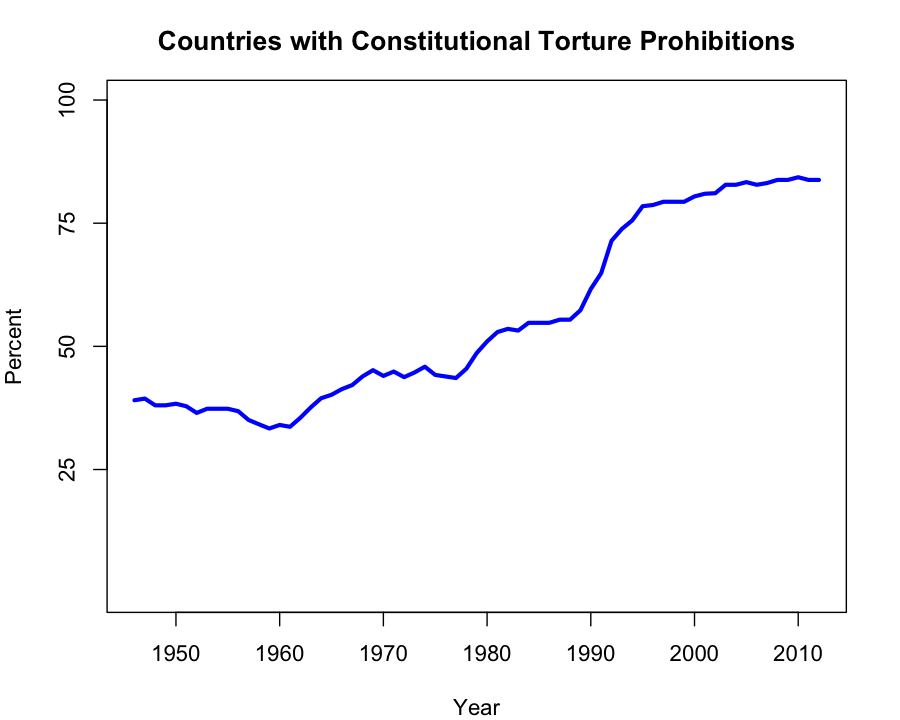

Before we conclude, pay attention to the dog that didn’t bark: Peltz’s failed campaign sends a strong signal to activists with similar goals as those Peltz tried to advance. If not before, then now they know: the combination of the index funds’ economic interests and voting power makes it unlikely that a campaign aimed at tougher competition will pass the ballot – so it might not be worth it to target a firm with these goals in mind in the first place.[4] That is how common ownership by “passive” funds can cause anti-competitive outcomes. If we want lower product prices, and higher output and efficiency, then taking a close look at the power and industrial organization of the asset management industry might be a good place to start.

[1] I haven’t gotten around to finding data on DuPont’s other product markets, which is why the following analysis is limited in scope and the external validity of its conclusions.

[2] Of course, this analysis does not prove that the passive funds voted against Peltz because he wanted DuPont to outperform the peers held by the passive funds, or because he criticized the voluntary wealth transfers to Monsanto and the lack of steep CEO incentives. Yet, whatever the reasons why the passive investors voted against Peltz, be it their economic incentives or other considerations, it is undisputable that their vote did prevent a campaign aimed at tougher competition. They thus caused less competition, compared to what it otherwise would have been.

[3] This outcome was indeed predicted. In this paper, my coauthors José Azar, Isabel Tecu, and I wrote: “owners generally need to push their firms to aggressively compete, because managers will otherwise enjoy a “quiet life” with little competition and high margins. Only shareholders with undiversified portfolios have an incentive to engage to that effect, while only large shareholders have the clout to do so. However, the largest shareholders of most firms tend to have diversified portfolios and therefore reduced incentives to push for more competition, whereas smaller undiversified investors don’t have the power to change firm policy without the support of their larger peers.”

[4] Opportunities abound for activist campaigns that didn’t or will never happen: very many U.S. firms are commonly owned by a similar set of diversified mutual funds as those owning DuPont and Monsanto. Here are a few examples.

Many academics consider it a professional obligation to write reviews of new books in their field. The reviews are published in academic journals which are hidden behind firewalls, so that they can’t be read by the public. And because most academics don’t read journals in other disciplines, an interesting book with cross-disciplinary appeal can easily be overlooked.

Many academics consider it a professional obligation to write reviews of new books in their field. The reviews are published in academic journals which are hidden behind firewalls, so that they can’t be read by the public. And because most academics don’t read journals in other disciplines, an interesting book with cross-disciplinary appeal can easily be overlooked.