A guest post by Adam Chilton:

A guest post by Adam Chilton:

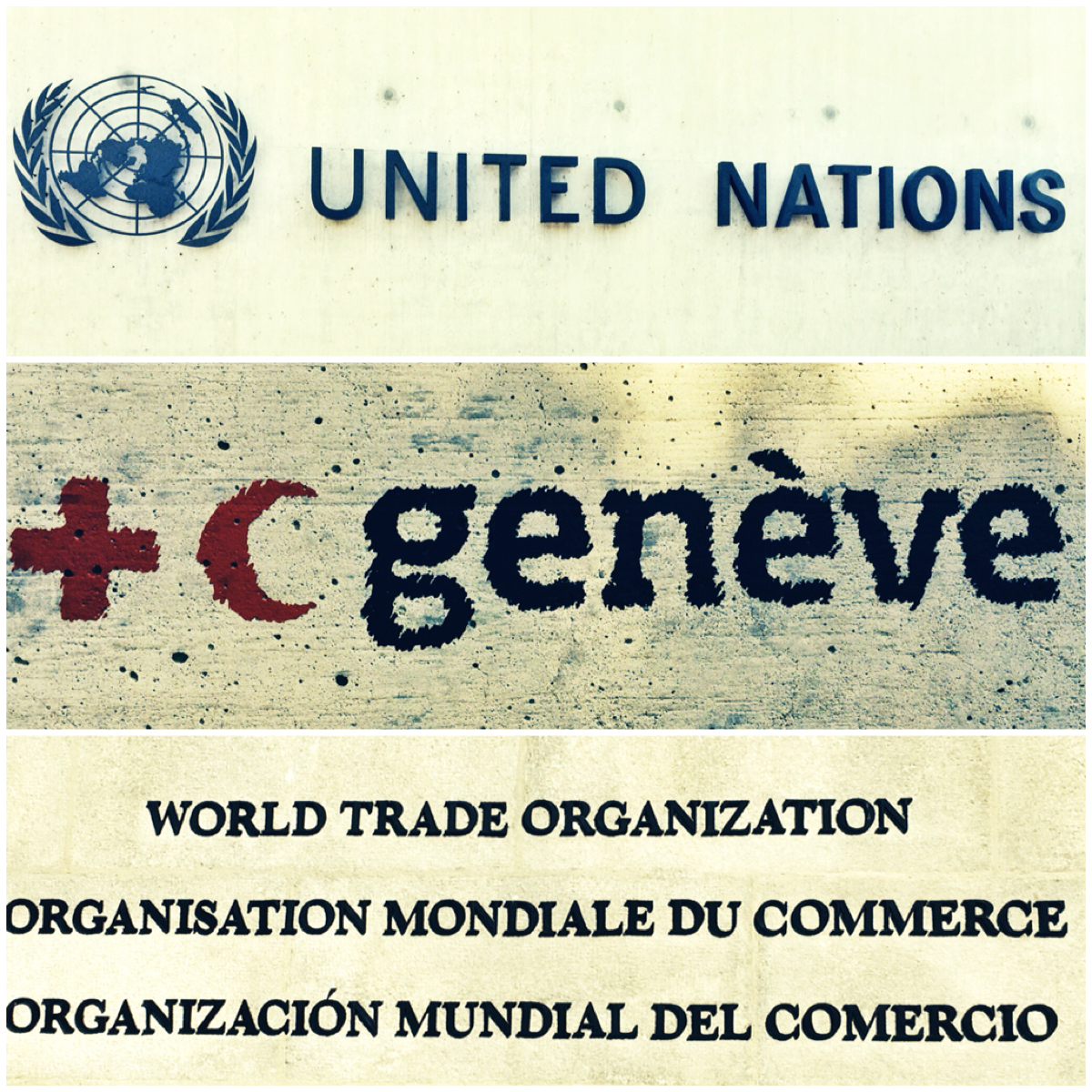

There are three pillars of international law: international human rights law, international humanitarian law (also know as the laws of war), and international economic law. Over the last week, I tagged along with a group of overachieving University of Chicago Law School students who decided to spend their spring break in Geneva visiting the international organizations most directly associated with each of these three branches of international law. When visiting these institutions, I was struck by how clearly each of their approaches to hosting visitors illustrates the mechanisms that scholars argue they use to change countries’ behavior.

The United Nations Human Rights Council (“HRC”) is a committee made up of 47 countries that tries to monitor the human rights practices of all countries that are members of the UN. The HRC meets in a large assembly room in the UN building in Geneva. The HRC’s room has seating areas for both the press and the public to watch their meetings, and webcasts all of the proceedings live. When we met with the HRC spokesman, he spoke about how social media engagement is one of the primary ways the Committee accomplishes its goals. The message was clear that HRC’s goal is to raise awareness of human rights abuses by engaging the public.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (“ICRC”) is the international organization that tries to monitor and promote compliance with International Humanitarian Law. Similar to the HRC, the ICRC headquarters in Geneva have public-facing spaces designed to make the work performed by the ICRC accessible to visitors. This includes a museum that documents the work of the ICRC and that outlines the major violations of the laws of war over the last century. The ICRC also runs courses for visitors on the basics of International Humanitarian Law. The ICRC’s goal is to clarify what is required of states during war, and to make the rules and violations well known.

The World Trade Organization (“WTO”) is an international organization that administers the international trading system. Unlike the other two organizations, the WTO does not offer daily tours or have an elaborate welcome center. Instead, visiting the WTO is a bit like visiting a law firm. You have to check in at a reception desk, and wait for an official to escort you into the building. We met with five WTO officials over two days. The officials were incredibly generous with their time, but I found it notable that not one discussed the importance of raising public awareness or how they utilize social media. Instead, the constant message was that the WTO system is increasingly weighed down by its own success. In short, too many countries are using the WTO dispute resolution system to adjudicate trade disputes and the organization is stretched thin trying to handle all of the cases.

For all three institutions, the way they engage the public reflects the mechanisms that scholars have agued that these bodies of law use to influence state behavior: international human rights law tries to raise awareness of abuses to create domestic political pressure for countries to improve their rights practices; international humanitarian law tries to clarify the obligations of states during war to create a common understanding of what practices are acceptable; and international economic law channels disputes into legal processes that are then enforced by reciprocal suspension of economic concessions.