I criticize them (especially law school human rights clinics) in a piece in the Chronicle of Higher Education, available here. My argument is that the political activism that takes place through these programs sits uneasily with university commitments to research and pedagogy. In the case of law school clinics, nearly any form of political activism can be justified as furthering “human rights law” because of the ambiguity of this term. Indeed, the term is, in practice, so capacious that clinics can engage in political activism under the banner of human rights law without teaching students any legal skills.

Make the U.S. More Like Qatar

That’s the headline given to a piece that Glen Weyl and I wrote for TNR. Migration is probably the greatest force for improving the well-being of the very poor, and hence for reducing global inequality. However, migration is extremely unpopular. Native workers fear labor competition, and everyone dislikes foreigners, with their strange ways, and fear that if foreigners settle and become citizens, they will vote their customs into law. (Europeans once assumed that their Muslim immigrants would adopt European attitudes toward women’s rights, personal freedom, and the like, but now fear and dislike them because they have not.)

The Gulf countries have cut this Gordian knot by allowing massive migration while granting migrants few rights and no political freedoms. It is obvious that these two polices are connected. The question is what we should think about them. (We in the US benefit from a similar system, albeit a de facto rather than de jure system, and much smaller on a per capita basis, with our 10 million+ illegal immigrants. By contrast 95 percent of Qatar’s population are migrant workers.)

The overwhelming view among elites, NGOs, and commentators is that the Gulf model is odious. The Gulf states should offer all their migrants the full panoply of human rights (and their citizens as well, presumably). But that’s not going to happen. And it seems likely, based on a comparison of us and them, that the rejection of migrants and the denial of rights are linked. And so the question is unavoidable: who (on a per capita basis) do more for the poorest people in the world: the authoritarian Gulf states with generous migration and no rights, or the democratic, human rights-loving but migrant-excluding West?

Vermeule: A Question about King v. Burwell

[N.B.: the entire post below is written by Adrian Vermeule, both the part in quotes, and the part that comes after it.]

Adrian Vermeule writes in:

Is the following an admissible legal argument? If not, why?

“Under Chevron, let us assume, the government wins so long as the agency offers a reasonable interpretation of statutory meaning, even if it is not clearly correct. The challengers have to show that the agency’s interpretation is clearly wrong, as a matter of the statute’s ordinary meaning.

So far nine federal judges have voted on the merits of the statutory challenge to subsidies on federal exchanges. (The nine comprise the six appellate judges who voted on the merits in King and Halbig; the two district judges in those cases; and one district judge in Oklahoma). To date, six votes have been cast in favor of the government’s position (some on the ground that the agency’s position is reasonable, some on the ground that it is clearly correct). Three votes have been cast against the agency’s view.

In light of these votes, to say that the statute has an ordinary meaning contrary to the agency’s interpretation verges on self-refutation. It implies that the judges in the majority of six can’t read English. It is logically possible that the sample of judges is severely biased in the government’s favor, but it is not actually true. The challengers have had broad latitude to choose their playing fields, and have been unable even to muster a majority of judicial votes, let alone the supermajority that would be necessary to suggest that the statute’s ordinary meaning clearly supports their case.”

Three notes:

(1) An admissible legal argument need not be conclusive, of course. The argument would have to be weighed against other admissible arguments.

(2) The argument, if admissible, would always counsel deference to agencies in Chevron cases where there is a circuit split, other arguments being equal. (Thanks to Abbe Gluck for this observation). I’m fine with that. Is it a problem?

(3) Another implication is that there should be no Chevron cases in which the agency loses by a 5-4 vote at the Supreme Court (and one may make appropriate modifications for other courts). In this setting, the legal rule itself specifies which party should win if reasonable disagreement is present: the agency should win. Accordingly, if a straw vote among the Justices shows a 5-4 split, then all the Justices should update their views; they should realize that there is reasonable disagreement in the case. If so, the agency should win 9-0. Under any other approach, judges in effect throw away valuable information — the information contained in their colleagues’ votes.

An earlier version of this post miscounted the votes, stating them as 5-4 in the government’s favor, instead of 6-3. Jonathan Adler, against interest, graciously corrected the record.

World Affairs Council talk on Twilight of Human Rights Law

You can watch me yammer away about Twilight of Human Rights Law here:

What can Obama do on his own?

Quite a lot (climate regulation, Guantanamo, immigration), I argue in Slate.

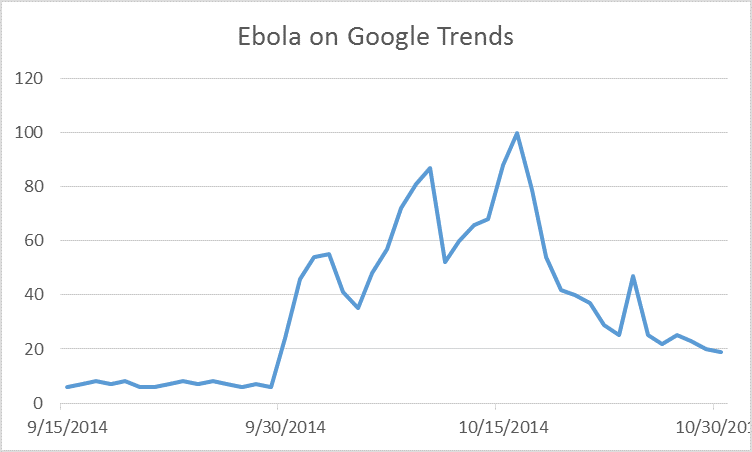

Is the Ebola panic over?

How to increase the supply of kidneys

Has International Human Rights Law Failed?

A hugely exciting conference on this theme will be held at the University of Chicago Law School tomorrow and Saturday. If you’re in the area, and would like to attend, you can register here.

Review of Scrap of Paper: Breaking and Making International Law during the Great War by Isabel v. Hull

A brief history of capital regulation in the US

Eric Holder

He marched down the trail blazed by John Ashcroft and Alberto Gonzales. Or so I argue in Slate.

The (real) legal case for bombing ISIS

I put together my thoughts at Slate. Incidentally, in the course of doing research for this piece, I ran across a large number of awfully confident claims that Obama’s decision to ask Congress for consent to use military force in Syria in 2013 meant that he, and possibly no other future president, could ever use military force unilaterally again. It did not take long for these claims to be falsified. All of the quotations below are taken from pieces written back in 2013.

Whatever happens with regard to Syria, the larger consequence of the president’s action will resonate for years. The president has made it highly unlikely that at any time during the remainder of his term he will be able to initiate military action without seeking congressional approval.

President Obama’s decision to seek authorization for military intervention in Syria is a watershed in the modern history of war powers…. The rest of the world can basically forget about the US going to military bat in these kinds of situations if congressional action is a precondition. This is a huge development with broad implications not just for separation of powers but for the global system generally.

In seeking congressional authorization, President Obama is thus re-submitting the modern presidency to the kind of “cycle of accountability,” to use Professor Griffin’s phrase, that the constitutional design anticipated. We will strike Syria, if at all, based on a joint determination by both elected branches that should nurture an ongoing sense of joint responsibility to monitor and assess in a careful way whatever consequences ensue.

In the NYT today I predicted that the President would be eating his words from the 2008 campaign trail to the effect that he needed congressional authorization for an intervention like the one planned for Syria. I was wrong, and I am very happy to say that I am now eating my words.

But not me.

President Obama’s surprise announcement that he will ask Congress for approval of a military attack on Syria is being hailed as a vindication of the rule of law and a revival of the central role of Congress in war-making, even by critics. But all of this is wrong. Far from breaking new legal ground, President Obama has reaffirmed the primacy of the executive in matters of war and peace.

Human rights law: A guide for the layperson

The list below has been compiled from the major human rights treaties, which have been ratified by the vast majority of countries.

***

Equality regardless of race, color, descent, or national or ethnic origin

Right to equal treatment before tribunals

Right to security of person

Right to effective protection and remedies

Right to freedom of movement and residence

Right to leave any country and return to one’s own

Right to nationality

Right to marriage and choice of spouse

Right to own property

Right to inherit

Right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion

Right to freedom of opinion and expression

Right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association

Economic, social, and cultural rights

Right to form and join trade unions

Right to housing

Right to public health, medical care, social security, and social services

Right to education and training

Right to equal participation in cultural activities

Right of access to any public place or service

Freedom from racial segregation

Prohibition of racist propaganda and organizations

Right of self-determination

Freedom to dispose of own wealth and resources

No deprivation of own means of subsistence

Inherent right to life

Restrictions and rights for anyone sentenced to death

General gender equality clause

Freedom of thought, conscience, and religion Prohibition of arbitrary arrest and detention Right to assembly

Right to privacy of the home

Right to association

Right to privacy of communication

Freedom of movement

Equal enjoyment of civil and political rights regardless of gender

Right of access to court and tribunals (habeas corpus)

Prohibition of torture

Right to vote

Prohibition of ex post facto laws

Freedom to choose residence

Freedom to leave any country

Rights of lawful alien in face of expulsion

Right not to be expelled from home territory

Equality regardless of race

Right to present a defense

Right to form trade unions

Right to counsel

Right to public trial

Right to review by a higher tribunal

Presumption of innocence until proven guilty

Rights regarding trial preparation

Freedom from forced testimony or confession of guilt

Right to establish a family

Prohibition of slavery

Freedom from forced labor

Right to liberty and security of person

Rights of arrested person

Rights for children

Right to a remedy when rights are violated

Right to personal privacy

Prohibition of double jeopardy

Equality regardless of belief/philosophy

Right to remain silent

Right to a timely trial

Equality regardless of political opinion

Right to an interpreter

Equality regardless of language

Right to ‘fair trial’

Right to work for the government

Right to privacy of family life

Minority cultural rights

Right to protection of one’s reputation or honor

Equality of husband and wife within the family

Right to appeal to higher court

Equality regardless of economic status

Equality regardless of nationality

Rights for prisoners

Right of self-determination

General gender equality clause

Right to education

Right to a fair wage

Right to work

Right to highest mental and physical health

Equality in employment promotion

Right to form and join trade unions

Right to establish a family

Right to social security

Right to protection and assistance to the family

Right to culture

Artistic freedom

Right to rest and leisure

Right to housing

Right to favorable working conditions

Right to protection of intellectual property

Right to strike

Right to adequate standard of living

Woman empowerment in labor relations

Right to maternity leave

Prohibition of child labor

Right to food

Right to take part in cultural life

Right to enjoy scientific progress

Legislative equality regardless of gender

Equality for women in political and public life

Prohibition of trafficking and prostitution of women

Equality of the husband and wife in marriage and family relations

Same right to enter into marriage

Same right to freedom in choosing a spouse and entering into marriage

Same rights and responsibilities

Same rights with regards to their children

Same personal rights as husband and wife

Same rights with regards to property

Right to acquire, change, or retain nationality

Equality for women in the field of education

Equality for women in the field of employment

Right to safe working conditions

Right to social security

Woman empowerment in labor relations

Right to maternity leave

Right to social services such as child-care facilities

Special protection during pregnancy

Equality for women in the field of health care

Equality for women in rural areas

Right to participate in development planning

Right to health care

Right to benefit from social security programs

Right to training and education

Right to self-help groups and co-operatives

Right to participate in community activities

Right to adequate living conditions

Prohibition of torture

Protection from extradition to another

State where danger of torture exists

Rights while in custody for alleged offense

Right to communicate with appropriate representative

Right to have national State immediately notified of the custody

Fair treatment in proceedings

Prompt and impartial investigation of an alleged act of torture

Rights for complainants and victims of torture

Right to complain about act of torture

Right to protection

Right to fair and adequate compensation

Prohibition regarding statements made as a result of torture

Prohibition of other acts of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment

Inherent right to life (for children)

Right to a name and nationality

Right to know and be cared for by parents

Right to preservation of identity

No separation from parents against child’s will

Protection from illicit transfer abroad and non-return

Freedom of expression

Freedom of thought, conscience, and religion Freedom of association and of peaceful assembly Right to privacy

Freedom from attacks on honor and reputation

Access to mass media information and materials

Right to physical and mental protection

Right to humanitarian assistance

Right to good health

Right to social security

Right to an adequate standard of living

Right to education

Right to rest and leisure

Protection from harmful employment

Protection from illicit use of drugs

Protection from use of children in drug trafficking

Protection from sexual exploitation and sexual abuse

Protection from torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment and punishment

Protection from abduction, sale, and trafficking

Protection from all other forms of exploitation

Protection from capital punishment and life imprisonment

Protection of children in armed conflicts

Prohibition of child labor

Best interests of the child as the primary consideration

Rights and duties of parents are respected

Rights for disabled children

Rights for minority children to enjoy own culture

Rights of children deprived of liberty

Rights of children accused of infringing penal law

Prohibition of death penalty

Equality for all migrant workers and their families

Free to leave any State

Right to enter and remain in their State of origin

Right to life

Freedom from torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment/ punishment

Freedom from slavery

Freedom from forced labor

Right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion

Right to opinions

Right to freedom of expression

Right to privacy

Freedom from unlawful attacks on honor and reputation

Freedom from arbitrary deprivation of property

Right to liberty and security of person

Right to protection

Freedom from arbitrary arrest or detention

Equal rights as nationals

Freedom from confiscation or destroying of legal documents

Freedom from collective expulsion

Right to protection and assistance by their State of origin

Right to recognition as a person

Rights regarding employment

Equal treatment and benefits as nationals

Rights to form or join trade unions

Rights to social security

Right freely to choose remunerated activity

Rights to medical care

Rights of child

Right to a name, registration of birth, and a nationality

Right to education

Right to learn mother tongue and culture

Right to a cultural identity

Rights upon termination of stay

Right to be informed

Right to liberty of movement

Freedom to choose residence

Right to participate in public affairs of State of origin

Right to political rights in State of employment, if granted Equal treatment with nationals of State of employment

Protection of unity of family

Equality in accessing education

Equality in accessing social and health services

Equality in participating in cultural life

Rights regarding taxes

Rights for family of deceased migrant worked or dissolution of marriage

Rights for arrested migrant workers and their families

Right to be informed about arrest in own language

Right to trial or release

Own State shall be notified of the detention

Right to communicate and meet with authorities in the own State

Right to a court trial

Victims of unlawful arrest or detention have the right to compensation

Right to be treated with humanity

Equal rights as nationals

Rights for accused migrant workers and their families

Right to be separated from convicted persons

Rights for juvenile persons to be separated from adults

Right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty Rights in the determination of criminal charges

Right to be reviewed by a higher tribunal

Freedom from imprisonment for failing to fulfill a contractual obligation

Rights for expelled migrant workers and their families

Rights for frontier workers

Rights for seasonal workers

Rights for itinerant workers

Rights for project-tied workers

Rights for specified-employment workers

Rights for self-employment workers

Rights regarding international migration

Rights to sound, equitable, humane, and lawful conditions

Rights to services to deal with questions

Prohibition of armed forces members aged <18 from taking direct part in hostilities

Prohibition of children aged <18 from compulsory recruitment into armed forces

Special protection for persons aged <18

Armed groups prohibited from recruiting or using in hostilities persons aged <18

Prohibition of the sale of children, child prostitution, and child pornography

Rights of child victims

Right to recognition of vulnerability

Right to adapted procedures to address special needs

Right to be informed of the proceedings and the disposition

Right to have views, needs, and concerns presented and considered

Right to support services

Right to privacy and identity

Right to safety

Right to avoid unnecessary delay in the proceedings

Assistance in recovery

Best interests of the child is the primary consideration

Equal protection and benefit of the law for disabled

Recognition of women and girls with disabilities

Recognition of children with disabilities

Access to public services facilities

Right to life

Right to protection in situations of risk

Access to justice

Right to liberty and security

Freedom from torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment/ punishment

Freedom from exploitation, violence, and abuse

Right to respect for physical and mental integrity

Right to liberty of movement and nationality

Right to live independently

Right to be included in the community

Right to personal mobility

Freedom of expression and opinion

Access to information

Right to privacy

Respect for home and the family

Right to education

Right to good health

Access to habilitation and rehabilitation services and programs

Right to work

Right to an adequate standard of living

Right to social protection

Freedom to participate in political and public life

Freedom to participate in cultural life, recreation, leisure, and sport

Protection from enforced disappearance

Rights for individual who alleges enforced disappearance

Right to report facts to authorities

Right to protection

Protection from extradition to another State where danger of enforced disappearance exists

No secret detention

Right to information on deprivation of liberty

Right to privacy of personal information

Rights for victims of enforced disappearance

Right to the truth

Right to reparation and compensation

Right to form and participate in organizations that address enforced disappearance

***

N.B.: some of the rights in this list appear more than once; the reason is that they appear in multiple treaties.

Duke’s New Human Rights Center

I received an email today announcing Duke Law School’s new Human Rights Center, Human Rights @ Duke Law:

Duke Law provides an integrated approach to human rights education, advocacy and scholarship that places students at the intersection of human rights theory and practice, domestically and abroad.

The Center includes a Human Rights Clinic. Its website says:

Types of clinic projects include those that: apply a human rights framework to domestic issues; involve human rights advocacy abroad; engage with international institutions to advance human rights; and/or address human rights in U.S. foreign policy.

Its new director says:

I am committed to enabling Duke Law students to make human rights work in a globalized world. This means developing clinic projects and practice opportunities that are both innovative as well as reflective of and grounded in sound and rigorous lawyering and legal analysis. By addressing the role of law and lawyers in engendering social change, the clinic and its students will advance the frontiers of human rights law and advocacy in ways that are smart, strategic, and impactful.

This sort of stuff is hardly unique to Duke. Many law schools have something like it: a Human Rights Center or Program explicitly devoted to advocacy as well as education and research, with a clinic through which students “practice” human rights law under the supervision of a lawyer. The only thing that distinguishes Duke is that they sent me spam about their program.

So I don’t mean to pick on Duke alone when I raise the following questions:

1. How many students actually do become human rights lawyers? Do the numbers justify the resources devoted to human rights centers and programs?

2. Is it appropriate to create centers in a university that combine research/education, on the one hand, and advocacy, on the other. Is it possible that a commitment to advocacy may interfere with research and pedagogical commitments?

3. What does human rights advocacy mean, anyway? Does it mean making claims based on the law, or does it mean making political and ideological arguments? Does it matter what these arguments are, or must they be connected in some way to a law school’s mission?

4. Is there a difference between “human rights” as a moral or political ideal, and “human rights law.” If so, do clinics pay attention to this difference?

5. Should law schools set up clinics that advocate for Christian ethics? Neoconservative ideals? The platform of the Democratic party? Are these missions different in kind from human rights?

6. Do law schools with Human Rights Programs–and other programs whose missions explicitly combine advocacy with education and research–monitor these programs in order to ensure that they act consistently with the law school’s mission, whatever it is? If so, do they issue public reports with their findings? If they do, I’d like to see them.

How many books on human rights were published in the last month?

By “books on human rights” I mean books with “human rights” in the title. The answer is at least 27, the number offered by Amazon when I checked yesterday. Amazon also offers 1,270 books on human rights that were published in 2013; and 18,960 books on human rights in total. (A spot check indicates a small number of false positives but the search is also underinclusive since it is limited to books with “human rights” in the title.)

Amazon does not sell all books. WorldCat, a large collection of library catalogs, lists 6,516 human rights books from 2013, and 166,891 in total.

But there’s always room for one more.

The Twilight of Human Rights Law

You can read an excerpt in Harper’s if you subscribe.

Marty Lederman’s brilliantly subversive defense of the president’s reliance on the 2001 AUMF

His argument boils down to the following points.

1. The administration’s legal theory is based on a factual predicate that might be correct (“the recent ISIL attacks are not unrelated to the AQ design of 2001, but instead part and parcel of that enemy’s design: that ISIL considers itself ‘the true inheritor of Usama bin Laden’s legacy’”). “Not unrelated”!

2. The administration adopted a legal theory that was less bad than the one “everyone” (?) expected (“a newly aggressive understanding of the President’s unilateral constitutional power to initiate military operations”). Most important, this theory keeps the ultimate authority in Congress’ hands.

3. Congress and the public support the military operation anyway (“this is a case in which the public and both houses of Congress do overwhelmingly support the President’s contemplated use of air strikes against ISIL, in Iraq and in Syria, but in which the leadership of the House has informed the Administration that the chamber is almost certain not to vote on the operation, for reasons other than substantive disapproval ”).

In sum, “a masterstroke that deftly threaded the needle without disregarding congressional will.”

A masterstroke, indeed. Here are thoughts about each of the points:

1. The president always knows conditions that justify military operations better than the public and Congress does. These conditions include not only the threat to Americans in a direct sense (an ISIS-sponsored terrorist attack on U.S. soil), which is derived from secret intelligence, but all the intricate, semi-secret implications for the security of allies, the proliferation of weapons, the dissemination of violent ideology, and so on—and here, of course, U.S. information about the actual structure of ISIS and its connections with other groups. The key point is that while the truth may ultimately come out, it will come out too late to affect Congress’ and the public’s capacity to stop a war before it begins. No way to sue the president for damages or obtain injunctions if the facts turn out the other way. And wars rarely stop, as we know from very recent experience, when the factual predicates are shown to be false.

2. Given the sort of interpretive latitude that Lederman grants the president, and effective deference to the executive branch’s superior information, the practical difference between a statutory argument and an Article II argument is vanishingly small. If you don’t believe me, sit down and read executive-branch opinions (some of them issued by OLC, some not, and some of them proposed but not officially adopted) on Haiti, Bosnia, Kosovo, Libya, etc. Adopting a “narrow” interpretation, closely tied to the facts and existing statutory authorities, in order to avoid broad legal assertions is meaningful only if the limiting language in the earlier opinions actually block subsequent action (they don’t) and old statutes can be repealed (apparently, they can’t).

3. This is really a political argument, not a legal argument, but it is worth noting that in Lederman’s hand it becomes a precedent that justifies the use of military force when the public and Congress “really” supports it, whether or not Congress acts officially through its voting procedures. Another loophole to be widened in future iterations.

What of the claim that Congress can turn around and take away the president’s authority—the great virtue of a statutory approach? But this would mean assembling a veto-proof majority in both Houses—which is not going to happen. Indeed, the opposite is more likely to happen—as has happened before (above all, Kosovo): Congress will be constrained to “support the troops” and vote for the money they need to continue operations.

You might have noticed that Lederman loaded his post with qualifications (“if this factual predicate is true,” “if that claim is true,” a “tentative case,” etc.), which in fact enhances the effectiveness of his defense. Nothing defuses a thundering jeremiad against the abuse of presidential power like a lawyer’s modest “it’s complicated.”

2001 AUMF? 2002 AUMF? New appropriations statute? Article 2??

Legal scholars are in a tizzy about the legal justification for the war on ISIS. Can’t the administration make up its mind? But Vermeule and I warned you years ago:

The main implication of this contrast is that crises in the administrative state tend to follow a similar pattern. In the first stage, there is an unanticipated event requiring immediate action. Executive and administrative officials will necessarily take responsibility for the front-line response; typically, when asked to cite their legal authority for doing so, they will either resort to vague claims of inherent power or will offer creative readings of old statutes.…

The overall picture of Congress’s role in emergency lawmaking, then, is as follows. Congress lacks motivation to act before the crisis, even if the crisis is in some sense predictable. Thus the initial administrative response will inevitably take place under old statutes of dubious relevance, or under vague emergency statutes that impose guidelines that the executive ignores and that Congress lacks the political will to enforce, or under claims of inherent executive authority. After the crisis is under way, the executive seeks a massive new delegation of authority and almost always obtains some or most of what it seeks, although with modifications of form and of degree. When Congress enacts such delegations, it is reacting to the crisis rather than anticipating it, and the consequence of delegation is just that the executive once again chooses the bulk of new policies for managing the crisis, but with clear statutory authority for doing so.

You could read Lawfare or Just Security every day. Or you could read The Executive Unbound just once.

Let Scotland go

Much ado about naething, I argue in Slate.

How could Obama rely on the 2001 AUMF to justify hostilities against ISIS?

Here is Ryan Goodman:

I have previously written that the 2001 authorization does not cover ISIS, and I noted: “As readers of Just Security, Lawfare, and Opinion Juris know, a remarkable consensus of opinion has emerged across our blogs that ISIS is not covered by the 2001 AUMF.”

Yet the White House ignored this remarkable academic consensus. Why? Well, remember the 2011 Libya war when the White House circumvented the War Powers Act by defining “hostilities” to exclude the act of raining down bombs and missiles on hostile troops? This broad interpretation of the 2001 AUMF is effectively a narrowing to nothing of the War Powers Act, henceforth, for all military activity directed against Islamic terrorists in the foreseeable future. Is it still possible to find this surprising?

The simple explanation is that in many settings–Libya, and, one supposes, this one–it is jointly in the interest of the president and relevant members of Congress to avoid a congressional vote that might force those members of Congress (specifically, Democrats right before an election) to go on record with a position that the party demands but their constituents reject.