A guest post by Will Baude, Adam Chilton, and Anup Malani.

At a recent symposium on Developing Best Practices for Legal Methodology, we proposed a set of principles for rigorous demonstration of claims about legal doctrine. Legal scholars, advocates, and judges commonly make such claims, we thought, but without a systematic demonstration of supporting evidence. One question we received from many of the participants at the symposium was whether this was indeed a common phenomenon.

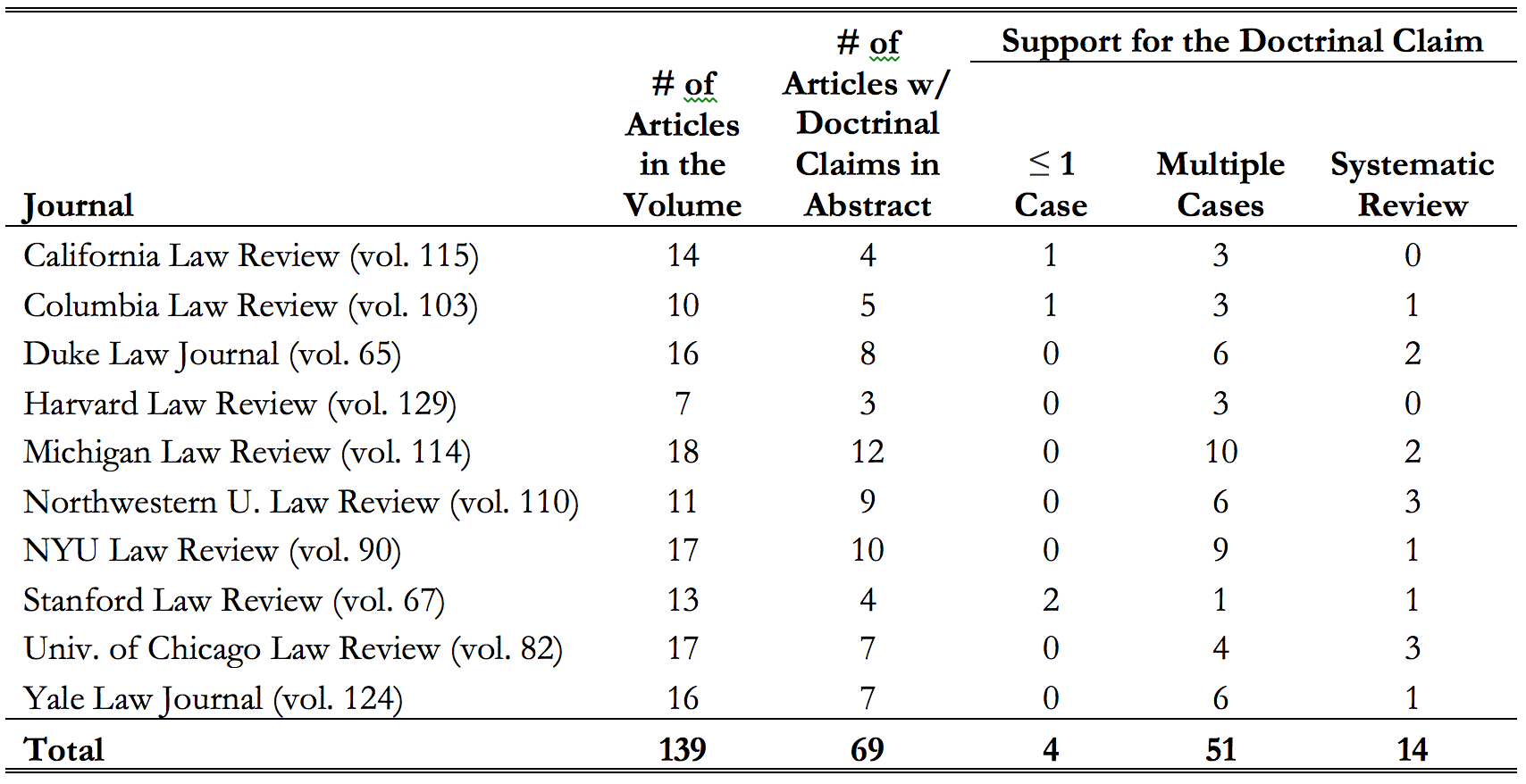

So to get a better sense of how frequently doctrinal claims are made without systematic support, we reviewed every article published in the last completed volume of ten top law reviews. For each article, we had a research assistant read the abstract and record any claim about the state of legal doctrine. The research assistant then read the article and recorded the evidence that was provided as support: at most a single case, multiple cases, or some form of a systematic review (that is, define the entire set of cases that was relevant to the claim and the evidence to support it).

The results of this review are in the above table. Our analysis suggested that roughly 50% (69 of 139) of articles included a claim about the state of legal doctrine in the abstract. Of these 69 articles, only about 20% (14 of 69) provided any form of systematic review to support the doctrinal claim. The rest of the articles provided string cites to cases (and occasionally, academic articles as well), but did not explain how they identified the universe of cases or whether they are representative.

This strikes us as suboptimal. To be clear, we have no particular reason to think that the doctrinal claims made in these articles are wrong. And we do not fault anybody for failing to adhere to a norm that does not yet exist. But our argument is that are important reasons that legal academia should develop a standard that helps legal analysts more rigorously document their claims about the state of legal doctrine.

Here are five reasons. First and most obviously, a more rigorous demonstration of evidence makes it easier for readers to evaluate the truth of a claim. Second, it is easier for readers to assess how confident to be in a claim. Third, it can prevent mistakes, even by experts. Fourth, it increases general progress in the field because it makes it easier for future research to build on the work from the past. Fifth, it helps reduce the risk or perception of bias.

Tomorrow we will present our proposal for how doctrinal claims can be made more systematically. If you are interested in reading more, you can read our essay on the topic that is now forthcoming in the University of Chicago Law Review.