Imagine that a group of amateur softball players start a game in a public park. An audience distributes itself on picnic blankets and enjoys the game. Question: should the audience pay the baseball players?

The answer, as a matter of culture, is no. And the audience certainly has no legal obligation to pay. We might say that the rule is: “if you play a game in the park, you cannot demand payment.” But is that a good rule?

Suppose the rule were: “if you play a game in the park, you may charge anyone who watches the dollar equivalent of the marginal product of your contribution.” This rule is, of course, impractical; but if it weren’t, it should produce social gains. Better players would migrate to the park, and consumers (that is what they are) would get a better product. A point I want to make is that the reason we have the inefficient rule is not just practicalities (of determining marginal products, regulating park usage, and all the rest). We also have a cultural norm that would frown on any player who tried to charge people who watched him play, with a partial exception for buskers, who (culturally speaking) are understood to be more in the business of entertaining, but still are not entitled to demand payment. The player, by contrast, is just having a good time. But isn’t he also “working”? A professional baseball player “works” when he engages in exactly the same activity. We don’t we say that the professional baseball player shouldn’t be paid because he’s just “playing.” What exactly is the difference between the amateur’s “work” (which we call “play”) and the professional’s “work”?

Now consider another setting: the family. Under the traditional conception of the family in our culture, the woman did not “work” in the sense that the man did. Of course, we have no trouble seeing housecleaning, dinner-making, and child-rearing as work, and even in the old days, people would sometimes resolve the cognitive dissonance by calling the work “women’s work,” thus devaluing it but not denying that it is work at all. You can even find judicial opinions where the work supplied by women in a household setting is treated as “gratuitous.” But the idea that women should not be paid for their work was entrenched. Married men, like the hypothetical baseball audience, enjoyed the benefits of a cultural monopsony.

We see this phenomenon in other settings. As Kim Krawiec points out in an ingenious article, the same cultural logic has been applied to the “gamete market”: women are expected to “donate” eggs for free, with compensation to cover only medical bills, rather than demand a fair payment. (Men, as sperm donors, are not.) We see something similar in the kidney market (for both sexes). The beneficiaries of the monopsony are not the ultimate consumer but intermediary companies, who are, by the way, (in the case of the egg market) being sued for price fixing. But there are countless examples. Sports—my original example, where the difference between “work” and “play” is so obscure—provide a long history of monopsony, mostly wiped out for now, except that universities operating through the NCAA continue to underpay “student” athletes who are essentially workers who are given room and board and a nominal education in return for extraordinary levels of labor. I suspect similar stories can be told in the area of the arts, ideas, and politics, where there have often been traditions of holding that workers should not be paid or should be underpaid. The common theme seems to be that firms have taken advantage of historical traditions and understandings that dissuade people from demanding full pay.

The latest and most interesting manifestation is the market for data labor. Starting with Jaron Lanier, commentators have pointed out that Facebook, Google, and other big tech companies have exploited a cultural understanding that when one uses internet services as a consumer one doesn’t “work” by supplying data despite the great value of the data for the internet companies, which use it to improve their AI services. This is not very different from my other examples, especially the women’s work example—since women were, in a rough sense, paid in kind for their work though not give their marginal product as they would in a market. The big tech companies would get better data if they paid people with money for their specific contributions rather than in kind through the general service provision (and, in fact, sometimes they do, but in a way largely hidden from the public, as when they hire people (as “workers”) to label photos), but very likely do not do so because they do not want to disturb the cultural monopsony from which they benefit. The result is that a huge number of people who make significant contributions to the development of AI and other services are unpaid, except roughly in kind, which not only retards the growth of technology services, but results in a massive transfer of wealth from ordinary people to the tech titans.

Glen Weyl and I explore these ideas in one of the chapters of our new book, Radical Markets, and argue that a free market in data labor would both advance technological progress and redistribute wealth to ordinary people. You can also read a discussion of the idea in The Economist.

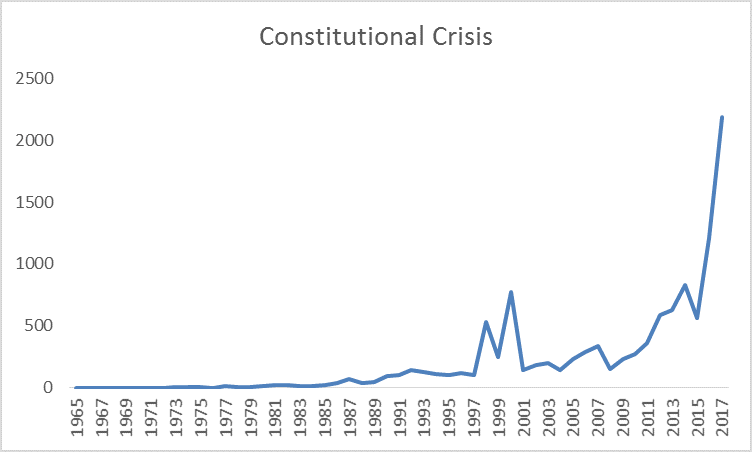

In this book, I examine the lawfulness of the federal government’s bailouts of major financial institutions during the crisis of 2008 and 2009. Probably of most interest to a specialist readership but I also address the broader inescapable issues of our system of government. Does the government have too much power? Are there ways to prevent abuse? You can preorder the book

In this book, I examine the lawfulness of the federal government’s bailouts of major financial institutions during the crisis of 2008 and 2009. Probably of most interest to a specialist readership but I also address the broader inescapable issues of our system of government. Does the government have too much power? Are there ways to prevent abuse? You can preorder the book