Over the last nine months I have been asked this question many times, and I always answer No. You might be unhappy with the presidency, or gridlock in Congress, or our constitutional system as a whole, but that is not the same thing as a crisis. If it were, then a constitutional crisis has always existed—it exists whenever someone we don’t like wins the presidency and since that’s always the case because people always disagree, that’s always. We might as well drop the term for something more descriptive—“constitutional unhappiness,” for example.

I was recently asked to write a chapter for a book, and was given the same question—is the United States in the midst of a constitutional crisis under the Trump administration? Again, my instinct was No. As I started a draft, I realized I would need a definition, and I tentatively began with this one:

First, there must be significant disagreement among political actors about what the constitution empowers or requires them to do. The disagreement cannot be merely theoretical (for example, over abortion rights, or the role of original meaning in constitutional interpretation); it must involve day-to-day operations. Second, this disagreement results in serious disruption in “normal” government operations or the substantial threat thereof.

The civil war was a constitutional crisis because North and South disagreed on the constitutionality of succession, and normal government operations were suspended for several years while the two sides battled it out. The contested 1800 and 1876 elections, and possibly the 2000 election, could also be considered crises, and also the Johnson and Clinton impeachments and Watergate as well, but at a much lower level. The disruptions of governance were briefer and less consequential, and the constitutional disagreements were not profound. The constitutional disagreements in Watergate and the 2000 election were resolved by the courts, and with the benefit of hindsight, we can see that both sides were willing to acquiesce in the Supreme Court’s pronouncements, suggesting that the constitutional disagreement was shallow. The impeachments may have disrupted the national government but they followed the constitutional rules.

The virtue of my definition is that it suggests that constitutional crisis is episodic rather than never-ending. But is the definition right? An alternative view is that a crisis exists just when people think it exists. And a lot of people seem to think that a constitutional crisis exists right now.

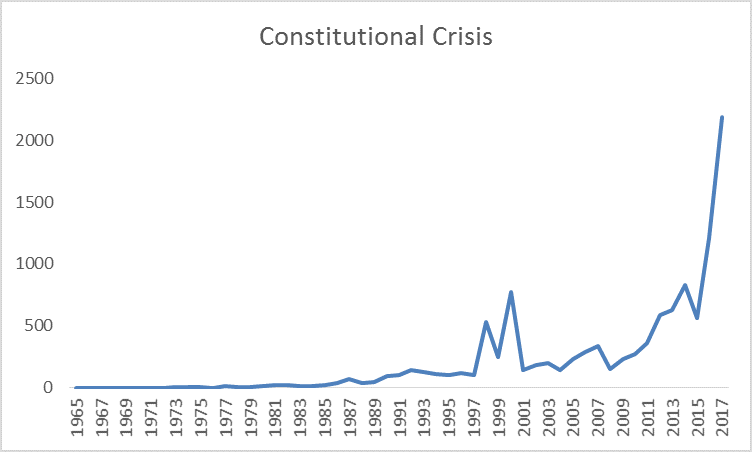

To address this alternative view, I adopted the very simple approach of counting up media articles that use the term “constitutional crisis.” The graph above provides the raw data.

Yow! If we go by the data, and we believe that a constitutional crisis exists if people think (or at least, say) it exists, the graph suggests that we are in one. The graph also gives us spikes during the Clinton impeachment and the 2000 election. But there is an obvious problem with using raw data, as suggested by the apparent flatness of the line during Watergate. It does not adjust for the increasing number of publications in the database.

The graph below shows the results after dividing the number of articles that contain “constitutional crisis” by the number of articles that contain the word “Congress” (possibly not the best denominator to use, I admit).

A few things stand out. Now we get the expected spike for Watergate, as well as smaller spikes for the Clinton impeachment and the 2000 election, and possibly for Iran-Contra scandal in 1987. Our current situation seems much less crisis-like but not exactly normal times either. This seems to me about right.

I think the problem with my narrow definition is that a crisis is in part a psychological phenomenon. A constitutional crisis could exist even if the government continues to function because people believe that at any moment it will stop functioning, or are willing to take action to stop it from functioning in order to vindicate their constitutional views—and that belief or motivation could itself precipitate the breakdown in the constitutional order. Have we reached that stage? Hard to say, but the data, for what it is worth, suggests not yet.